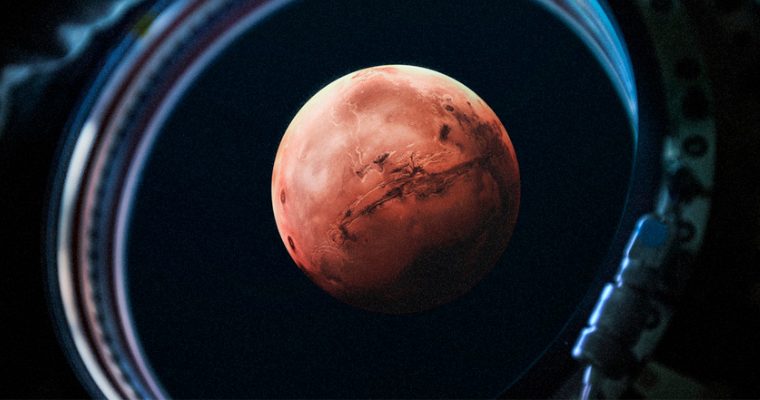

Tests are underway on a rocket technology that could vastly shorten the time it takes for humans to get to Mars, greatly reducing the risk of mechanical failures and other deadly space hazards on future Mars-bound astronauts.

Costa Rica and U.S.-based Ad Astra Rocket Company announced over the summer that it had completed a record 88-hour high-power endurance test of its Vasimr VX-200SS plasma rocket at 80 kW. The test, conducted at the company’s Texas laboratory near Houston, constituted a new high-power world endurance record in electric propulsion.

‘Years of trial-and-error testing’ for Vasimr rocket

“The test is a major success, the culmination of years of trial-and-error testing and painstaking attention to detail and a handsome reward for the team’s tenacity and dedication,” said Franklin R. Chang Díaz, Ad Astra’s chairman and CEO, who flew on seven separate missions as a NASA astronaut, logging 1,601 hours in space.

The Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (Vasimr) rocket was designed to fly with an engine that uses nuclear reactors to heat plasma to two million degrees. Hot gas is then channeled, via magnetic fields, out of the back of the engine to propel it, in theory, at speeds of up to 123,000 mph (197,950 km/h).

The goal for Ad Astra is to make much faster, but also much safer spaceflight possible — despite the fact that Vasimr rockets would send nuclear reactors hurtling through space at incredible speeds. Though Vasimr launch vehicles will still require chemical rockets to reach orbit, once there, the plasma engine (described in the video below) will be engaged, greatly improving the safety of the crew, according to the company.

Four times faster than existing chemical rockets

In the seven months NASA estimates it would take to fly humans to Mars, any number of catastrophic failures could occur. That’s why Díaz said in a 2010 interview with Popular Science that “chemical rockets are not going to get us to Mars. It’s just too long a trip.”

A conventional rocket must use its entire fuel supply in a single controlled explosion during launch before propelling itself towards Mars. There is no abort procedure, the ship will not be able to change course, and if any failure occurred, mission control would have a 10-minute communications delay, meaning they could find themselves helplessly watching on as the crew slowly dies.

Ad Astra’s plasma rocket Vasimr, on the other hand, will sustain propulsion throughout the journey to the red planet. It will accelerate gradually until it reaches a maximum speed of 34 miles (54 km) per second by the twenty-third day, making it four times faster than any existing chemical rocket. This would reduce that estimated seven-month journey by approximately six months.

Less time traveling through space means less exposure to solar radiation — a recent study states that Mars missions should not exceed four years for crew safety — less risk of mechanical failures, and less of a health risk due to the muscle atrophy effects of zero-gravity. As the ship’s plasma engine can provide propulsion at any time, it could also change course if required.

Following Ad Astra’s successful plasma rocket endurance test in July, the company announced its plans for the future. “With a new set of engine modifications already in the manufacturing stage, we’ll now move to demonstrate thermal steady state at 100 kW in the second half of 2021,” Díaz said in Ad Astra’s press release.

Other firms such as DARPA are also developing nuclear-powered rockets — the Pentagon agency announced this year that it wants to demonstrate a nuclear thermal propulsion system above low Earth orbit in 2025. Spaceflight looks like it’s on course to go nuclear, in a move that would greatly enhance humanity’s capacity to launch to unexplored regions of our universe.