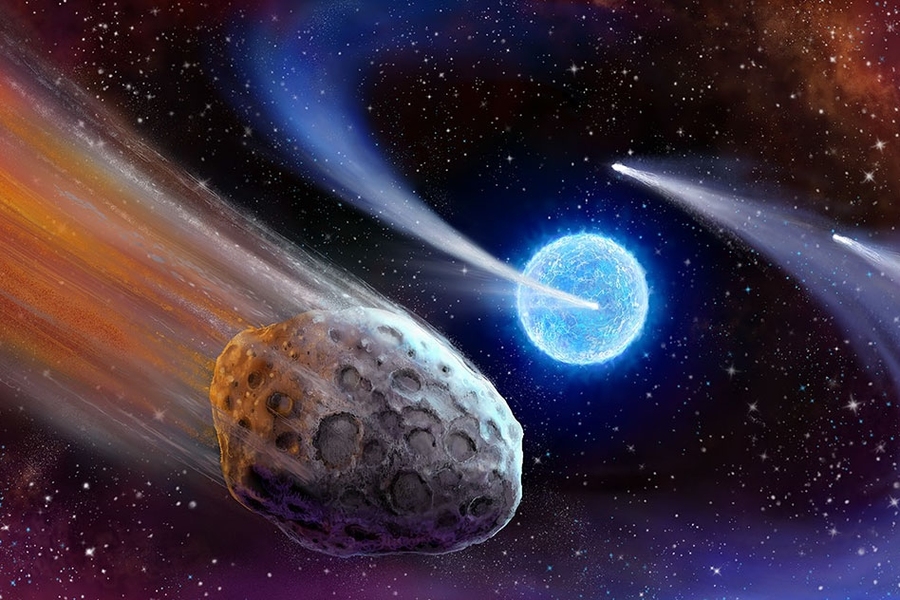

There was no Palomar Observatory when the object now known as comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) made its last close approach to Earth 50,000 years ago. There were mastodons and woolly mammoths, and great swaths of glaciers covering portions of North America and northern Europe, as the planet went through its last ice age. But there were no trained skygazers. Now, the ghostly green comet, spotted last year by two modern-day astronomers working at Palomar, in southern California, is swinging back our way. This week, the comet is heading for a close approach to Earth on Feb. 1 and 2, when it will be just 43 million km (27 million mi.) from our planet and be visible to the naked eye as a bright green smudge in the northern hemisphere’s skies.

The researchers credited with discovering C/2022 E3 (ZTF) on March 2, 2022 are Bryce Bolin, a NASA postdoctoral fellow at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and Frank Masci, a senior scientist at Caltech, in Pasadena, Calif., the first humans or human-like beings (after the homo sapiens and Neanderthals of 50,000 years ago) to have seen the object—and initially they weren’t looking for comets at all.

The ZTF in the comet’s name stands for Zwicky Transit Facility—essentially a very sophisticated camera and computer attached to one of the telescopes at Palomar. The system is programmed to look for exotic objects outside the solar system and even the galaxy—like supernovas, emerging black holes, and pulsating stars, all of which appear as discrete points of light.

Comets, however, have a different optical profile: by the time they’re close enough to see by telescope, they appear as a larger, fuzzier blob, not the tiny dot the ZTF is trained to identify, so the facility was just discarding those images. To Bolin, who has discovered 50 comets during his time observing the skies, that would not do.

“This was a problem, where photons were falling to the ground,” he says. “We were wasting precious potential comet photons from reaching us through our data system.”

“There’s a lot of moving parts that have to come together to make it all happen,” Bolin says. “Not only do you have the data system we worked on, you also have the people who set the telescope, the people who designed the telescope and built it, and so on. It’s like 100 people are involved.”

The precise spot to look in the northern sky as the comet approaches is very much a moving target, visible only at night. On Jan. 23, as Space.com reports, C/2022 E3 (ZTF) was near the constellation Draco below the Little Dipper; on January 26, it was just beside the Little Dipper itself. On Jan 30, through its closest approach to Earth on Feb. 1 and 2, it will be visible near the constellation Camelopardalis, just past the point of the Little Dipper’s handle. (See TheSkyLive.com for the exact visibility from your location.) Then, the comet will begin making its outward-bound journey, resuming its long, looping transit back through the solar system, not to return to us for another 50 millennia.

source:time.com