Infotainment has to be our favorite way to spend our coffee breaks and commutes. Equal parts informative and entertaining, it’s the kind of internet content that instantly hooks you in and doesn’t want to let go.

The next thing you know, you’ve spent the last couple of hours reading Wikipedia, jumping from articles about science and the animal kingdom to analyses of historical events and art movements. A single quality social media post can reignite your curiosity and remind you just how much fun it can be to learn new things about the world.

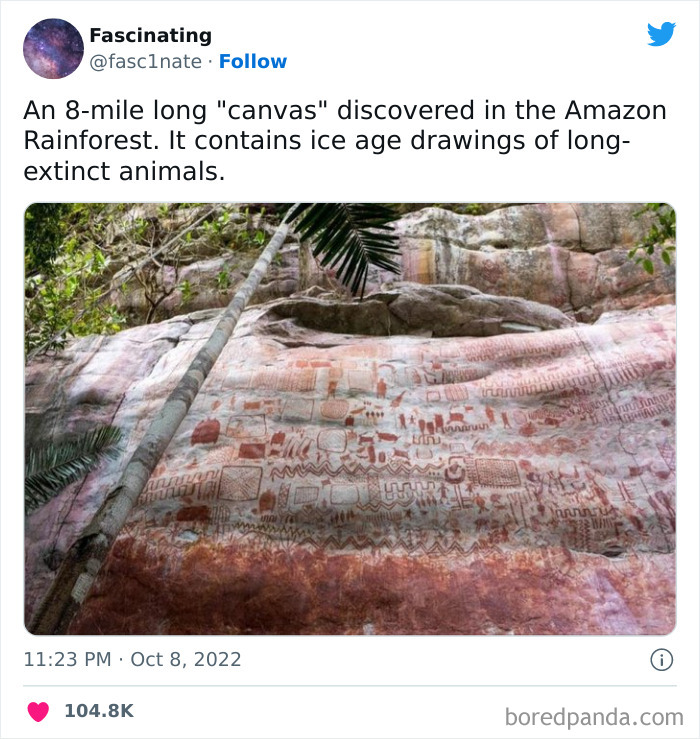

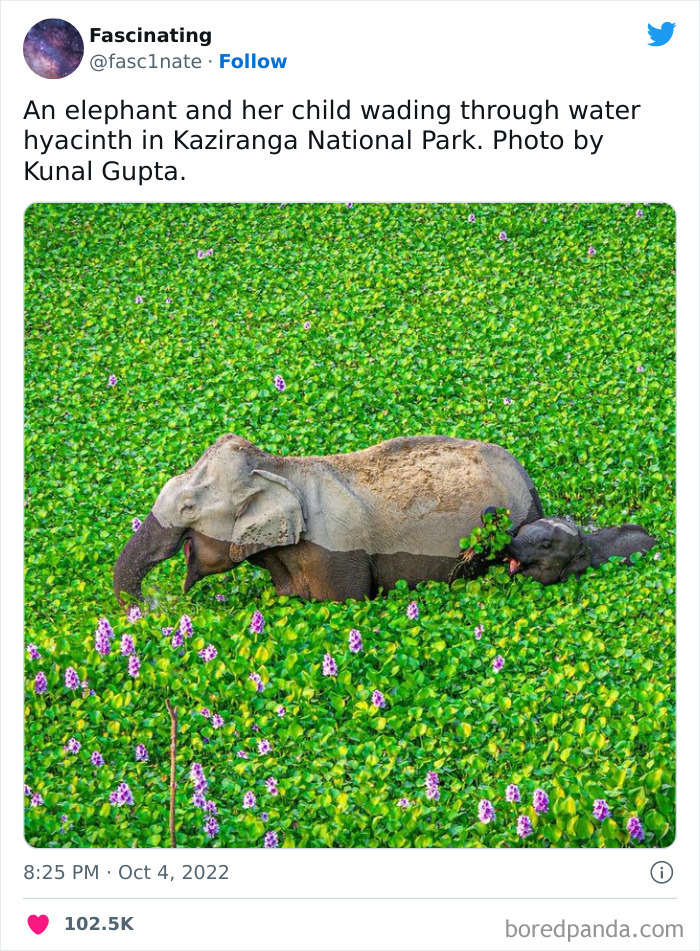

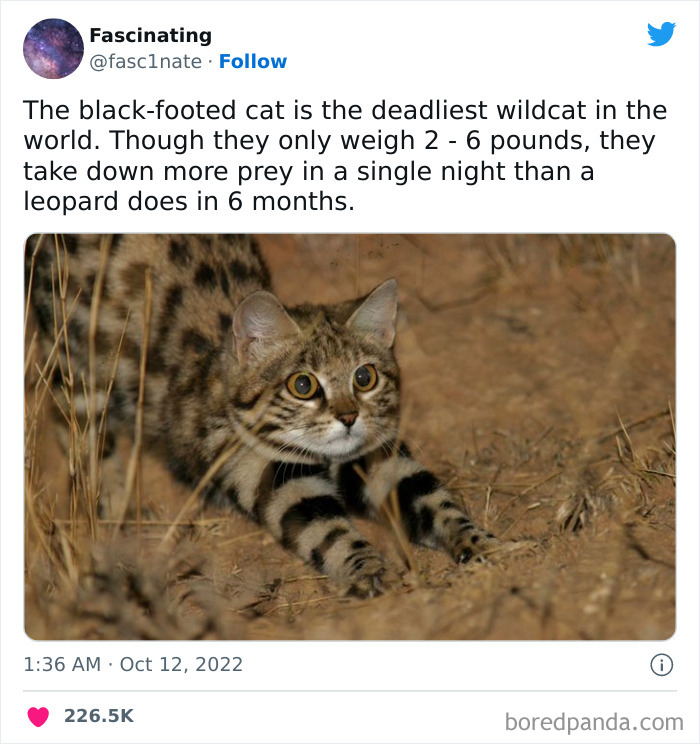

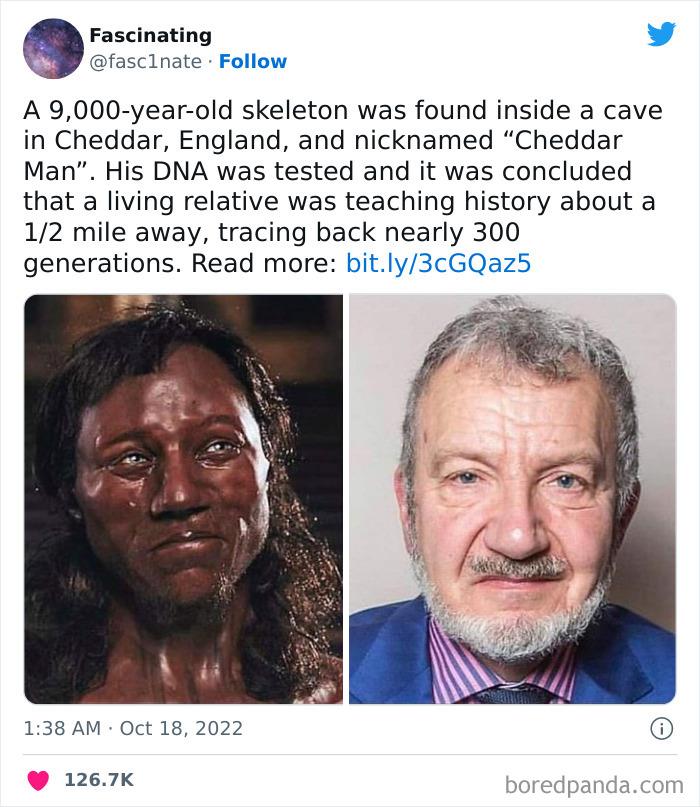

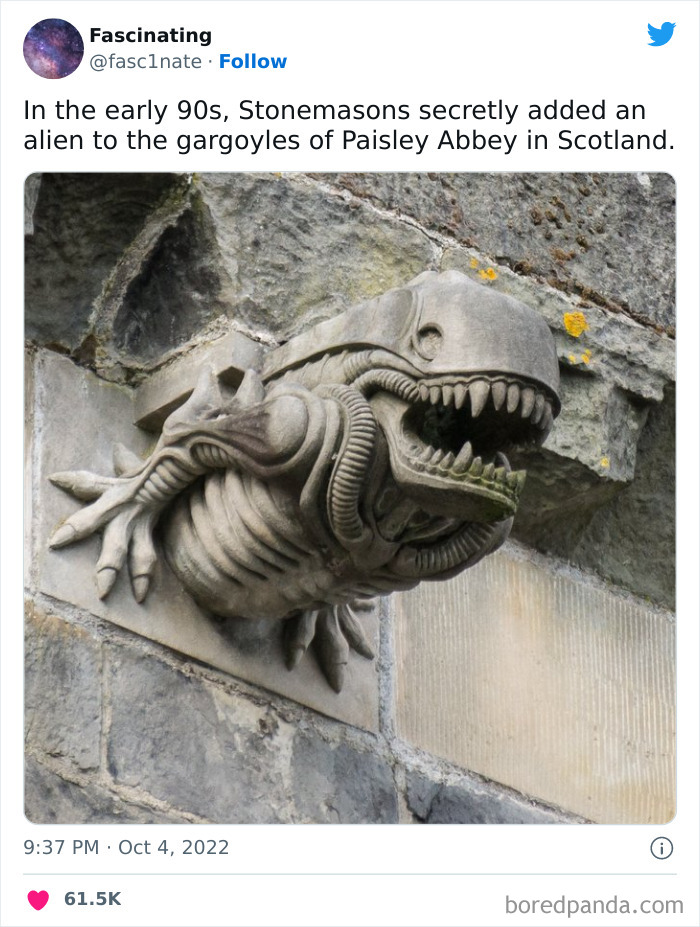

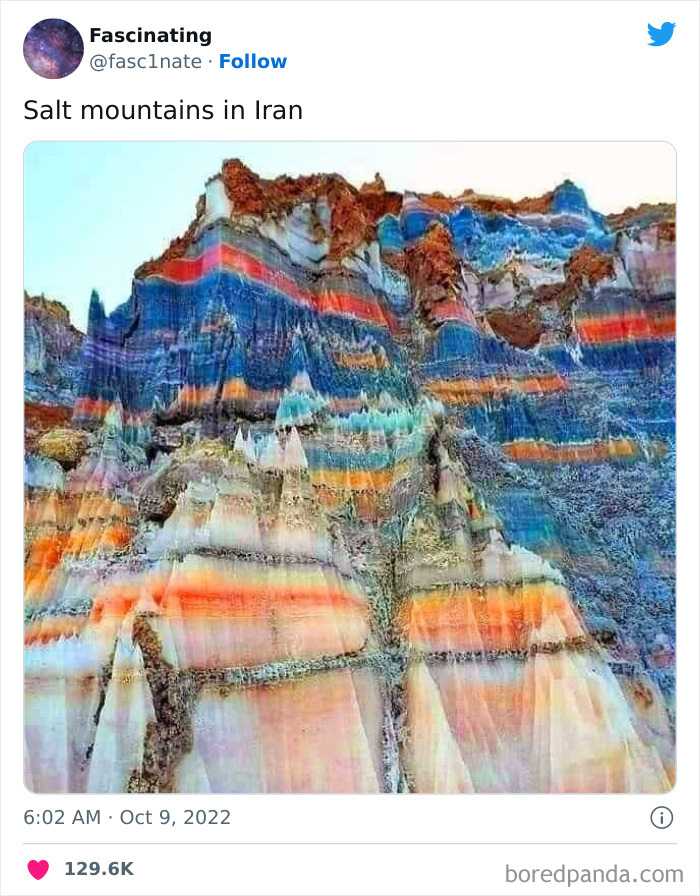

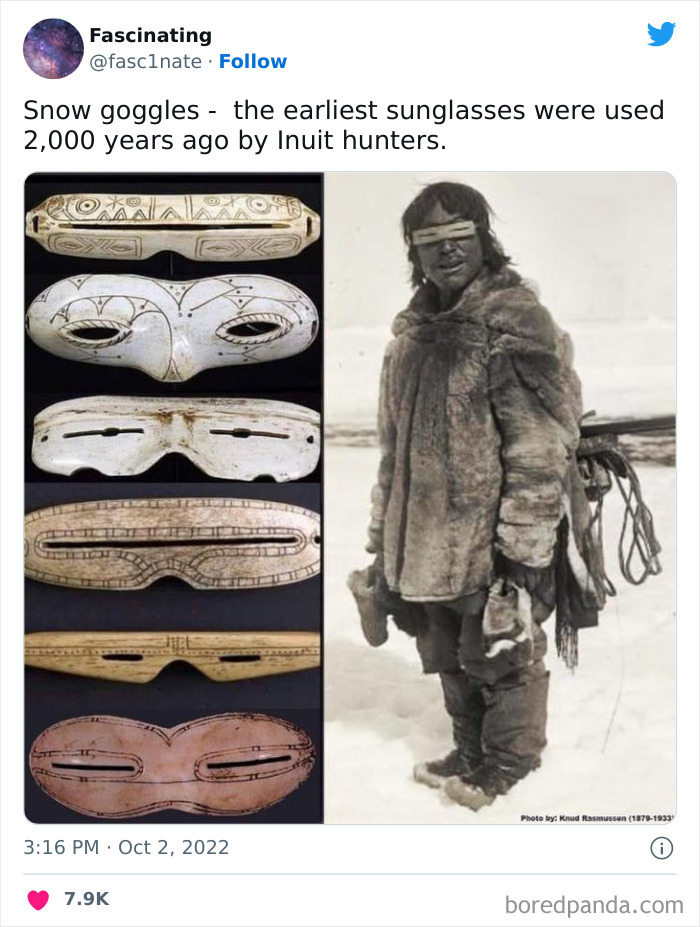

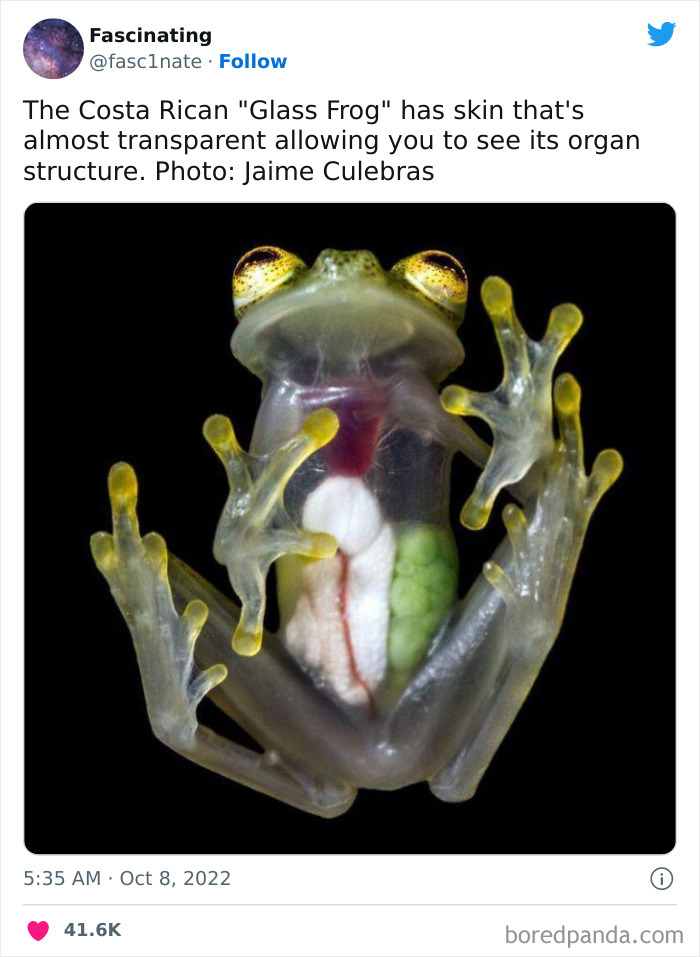

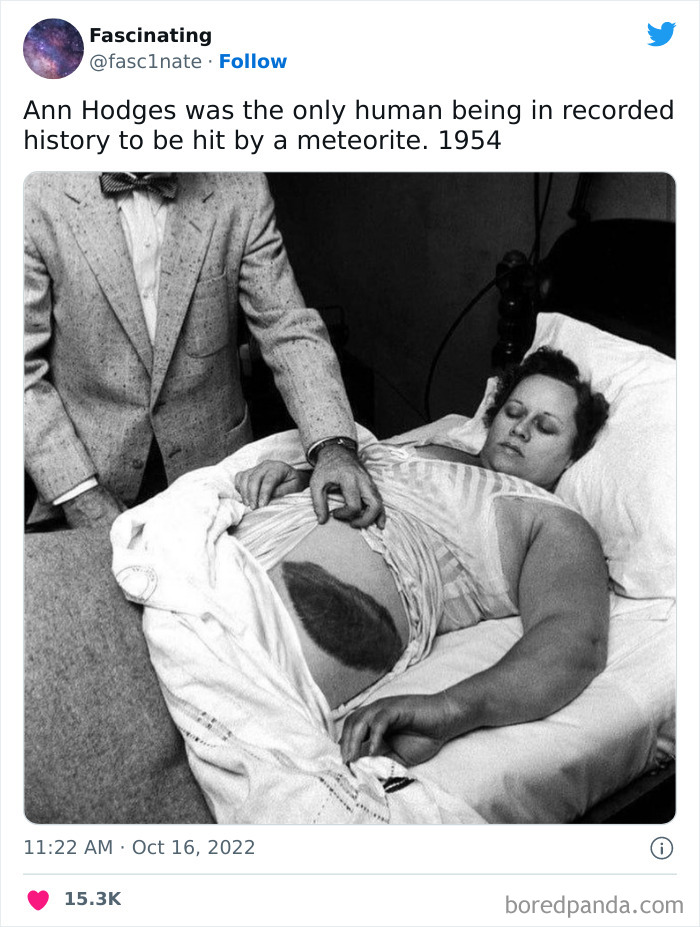

The popular ‘Fascinating’ Twitter page, aka @fasc1nate, is home to some pretty interesting science, history, and art facts from around the world. We’ve collected some of their coolest pics and most mind-blowing facts to share with you today. You’ll find them below, so scroll on down and upvote the pics that got your attention the most. Go on, take a break, and have some educational fun. You deserve it.

#1

Bored Panda wanted to understand the things that people should not do when interacting with wild wildlife. Dr. MacDonald, from York University, said that the best way to deal with wild animals is “to NOT FEED THEM.” If you don’t follow this rule, it leads to problems that “will inevitably result in their early demise.”

So remember, Pandas, no feeding the wildlife… no matter how cute the animals look. Promise?

“I think benign co-existence should be the goal,” the animal behavior specialist told Bored Panda that humans and wildlife should follow a “live and let live” philosophy.

#2

#3

We were also interested in how animals of different species get along in the wild, and if there’s a constant struggle for resources and territory. Dr. MacDonald told Bored Panda that it all depends on the species.

“Predators and their prey are locked in a constant battle. Other species, that occupy the same territory and search for the same food types (like skunks and opossums, for example), generally tolerate each other unless food is scarce, in which case they will compete,” the animal behavior expert said.

#4

#5

#6

“It is within a particular species that most competition occurs—for space, food, water, mates, territory. So for example, raccoons compete with other raccoons for all those things, and that’s where you see the most conflicts. They rarely escalate to fights-to-the-death, though, and are mostly about establishing dominance through who can make the most noise and look the most intimidating.”

Created nearly a decade ago, all the way back in February 2013, the ‘Fascinating’ Twitter project has amassed over 216.5k followers in that time. The content shared resonated with a lot of people because it mixes photos that instantly grab their attention with bite-sized facts.

Their posts are a good starting point for someone hoping to look into a topic, whether it’s about animal behavior, plants, ancient archeology, or anthropology. We feel that as long as you’re interested in the world and learning something new, life continues to be a lot of fun.

#7

#8

#9

However, just because something’s posted online, has a pretty picture attached to it, and has gone viral, doesn’t automatically make it the truth. Part of living in the 2020s and navigating the digital landscape means that media and internet literacy should be given more attention. In short, this means checking the reliability of the source and verifying facts before pressing the like and share buttons on whatever social media platform you use the most often.

Many cool facts really do end up being true. However, social media also means that misinformation can (be) spread quickly, too. Whether intentionally or completely by accident.

Recently, Bored Panda had a chat about verifying the reliability of information with scientist Steven Wooding, a member of the Institute of Physics in the UK and part of the Omni Calculator team.

“If a claim comes from a single source (whether it is an authority figure or not), you have to be quite skeptical,” he told us.

#10

#11

#12

“Even if there are loads [of independent sources], they may have gotten locked into a ‘groupthink’ situation, and the claim is actually false. We should never have blind faith in authority figures. There is always a chance they could be wrong,” he explained that far from everything that we see, read, and hear is true.

Experimental bias and cherry-picking results are some of the most common ways that authority figures might mislead others.

#13

#14

#15

“Often you just need to look at who funded the research. It’s not surprising that (in the past at least) research funded by a maker of cigarettes said that their product was safe,” the scientist told us.

While skepticism is important, too much of it can be detrimental to scientific efforts and progress. There has to be a reasonable balance between outright skepticism and blind faith in authority figures.

#16

#17

#18

“If the public were very skeptical, science would be hindered, and progress slowed. In areas such as healthcare and technology, science is delivering for people and making a difference in their everyday lives,” the scientist told Bored Panda.

“In the past few decades, [faith in the scientific community] has probably increased. Climate change is now more widely accepted than ever before now that its effects are clear to see. And science has got the world through the recent pandemic with innovative vaccines, anti-viral drugs, and data science,” he said.

#19

#20

#21

A while back, Lee McIntryre, from Boston University, spoke to us about media literacy. He pointed out that just because a fact or claim is constantly repeated doesn’t make it true.

“Repetition is important in making us believe things, whether they are true or not. There is a cognitive bias called the ‘illusory truth effect’ which is when we are repeatedly exposed to false information over and over and, over time, it begins to seem more plausible,” he said.

#22

#23

#24

“Social psychologists have known since the 1960s that repetition works, for truth or falsity. In fact, this idea goes back to Plato who said that it didn’t hurt to repeat a true thing,” the expert said, warning that some might use this effect as a way to spread propaganda, as they have in the past century to horrible effect.

Even well-educated individuals aren’t immune to making mistakes. For instance, someone might intellectually understand how the illusory truth effect works and how repetition ties into it. However, in real life, they might fall victim to it without even realizing it. Cognitive biases are an ever-present danger, even if we understand them.

#25

#26

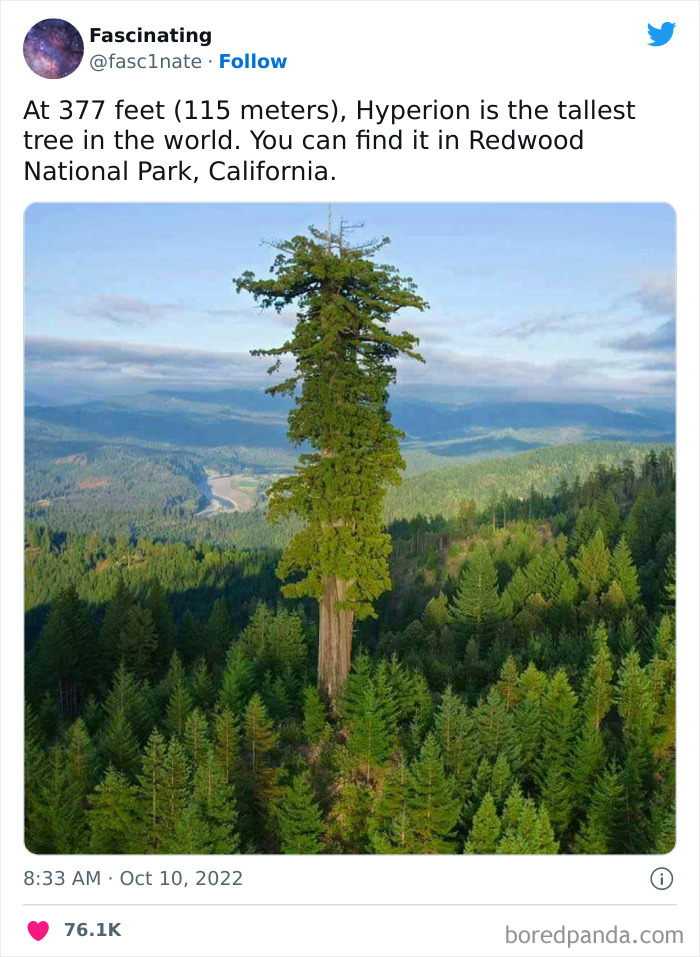

Either Hyperion has hyperactive growth hormones, or it was the lone survivor of an ancient wildfire, and everything else around it is new growth (in comparison). Arborists/Botanists are welcome to let me know why it’s so much taller than the surrounding forest.

Either Hyperion has hyperactive growth hormones, or it was the lone survivor of an ancient wildfire, and everything else around it is new growth (in comparison). Arborists/Botanists are welcome to let me know why it’s so much taller than the surrounding forest.

#27

“It would be exhausting to fact-check every single news item we hear. In fact, insisting on this degree of skepticism is something that demagogues use to get us to be cynical, because when we doubt that it is possible to know the truth—even when it is staring us in the face—we are riper to their manipulation. So I’d say the best thing with news is to do a little investigation into finding a reliable source,” Lee told Bored Panda.

“Look for an organization that does investigative journalism (and doesn’t just repeat information from other sources), double sources its quotations, discloses conflicts of interest, etc. Once we’ve found that we can relax a bit and trust the reporting behind the stories. Do we still need to be on guard? Yes. Even The New York Times can make mistakes. Or individual reporters can have biases. But that doesn’t mean ‘all sources are equal.’”

#28

#29

#30

Some of the questions we need to ask when considering any claim or source include: “Is the story copyrighted? Is it dated? Is there a byline? Are other stories by the author solid? Is it published in a source that has been reliable in the past? Does it seem plausible—if not then you can do some research,” Lee explained.

“Will we get fooled sometimes in doing this? Yes. But we’re going to get fooled sometimes anyway. It’s analogous to how scientists form their beliefs. They are skeptics, but they also—at some point when the evidence is sufficient—give their assent. Scientists deal with warrant, not ‘proof.’ They are what philosophers call ‘fallibilists.’ You give your belief to things that are well-sourced with evidence, while always holding out the possibility that if further evidence comes to light that contradicts your belief, you should give it up because you might be wrong.”

#31

#32

#33

#34

#35

#36

#37

#38

#39

#40

#41

#42

#43

#44

#45

Soυrce: bestartzone