Israel has pretty much written the book on using light unmanned aircraft to obliterate enemy air defenses.

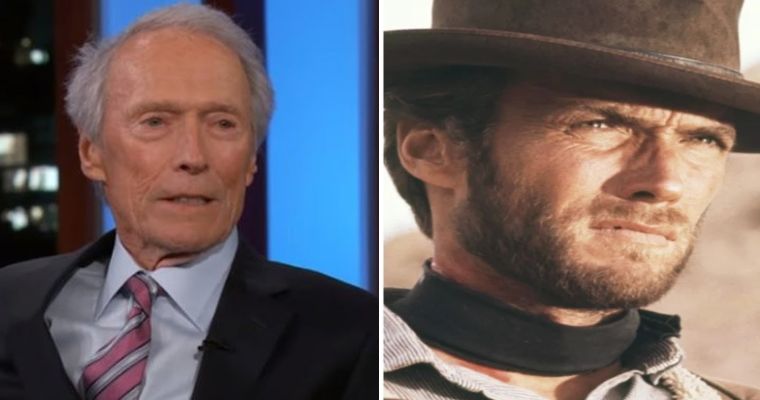

When you first see Israel Aircraft Industries’ Harop drone, the “Star Trek” association is unmistakable. Like the Klingon Bird of Prey it resembles, the Harop is small, maneuverable, nearly impossible to detect, relatively inexpensive, and is downright deadly. And when it comes to accomplishing its mission, it even operates on the belief that “today is a great day to die.”

The diminutive drone doesn’t carry any munitions; it doesn’t need to, because it is the munition. A 50-pound high explosive charge is part of the Harop itself, and if it finds an enemy radar or another target of opportunity in its vicinity, it will creep up, and once close enough, dive right into it, blowing itself and the target to bits in the process.

Harop is primarily a Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) weapon system, used to neuter an enemy’s radio frequency-emitting sensor capabilities. Using drones to help destroy and confuse an unfriendly air defense network is something Israel knows a lot about, as they’ve been using them to do just that since the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

During the conflict, the Israeli Air Force used Firebee and Chukar drones furnished by the US to distract, confuse, and stimulate enemy radar—much like the US had in Vietnam. The tactics helped blunt Israeli combat aircraft losses, and clearly, the IAF knew they were onto something.

Following the Yom Kippur War, Israel began manufacturing their own simple unmanned aircraft, most of which had the same twin tail-boom configuration as many modern (and much larger) unmanned aircraft flying for the IAF today. But these were far simpler systems, with lower performance than the Chukars and Firebees used in combat in 1973. But what they lacked in performance they made up for in expendability and numbers.

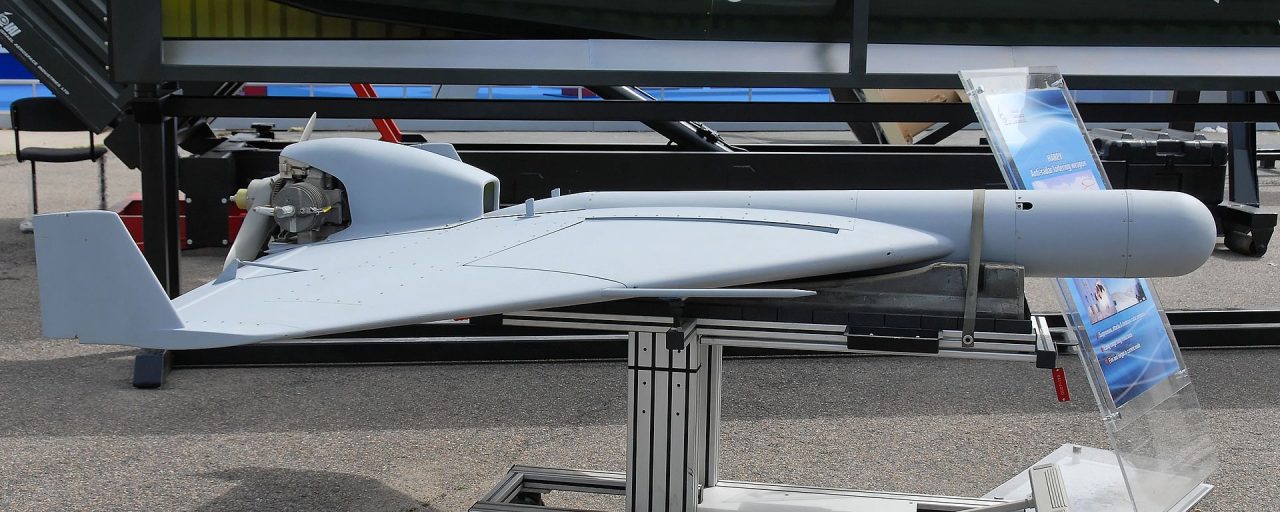

Harop drone on display at the 2013 Paris Air Show., Julian Herzog

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the IAF’s growing armada of unmanned aircraft was flying missions over Lebanon, surveying for Syrian air defense batteries and military emplacements. Some were shot down by the growing surface-to-air missile system network being installed by Syria in the region. But that didn’t matter, since the designs were built for high-risk and even one-way missions.

In 1982, when open hostilities broke out in Lebanon, Israel put its drones to use on a massive scale. It was dubbed Operation Mole Cricket 19—the plan to rapidly eradicate Syrian air defenses in the Bekaa Valley. In just a matter of hours, it did just that.

Israeli Mastiff drone, like the ones used during the Mole Cricket 19 operation., Bukvoed/wikicommons

In the afternoon of June 9th, drone after drone flooded into the Lebanese airspace, acting as decoys that would bait Syrian air defenses into activating their radar systems. This allowed Israeli fighters to swoop in and launch anti-radiation missiles and direct attacks on the radar and/or surface-to-air missile sites, and get away unscathed.

Scout and Mastiff drones were used in the highly technical and ground-breaking operation. It was the first time western hardware had totally eradicated a Soviet-designed and furnished integrated air defense network. Without radars, SAMs were useless and vulnerable to attack. Additionally, Syrian fighter pilots, trained under the Soviet doctrine that centered around direction from ground-based radar intercept controllers, were essentially blind. Selective jamming by the IDF of Syrian Air Force radio frequencies made them even more vulnerable.

Israeli unmanned air vehicles were even stationed over Syrian airfields to watch as MiGs took to the skies. This information was immediately passed on to orbiting E-2C Hawkeyes that directed Israeli fighters to engage the emerging fighters.

With Israeli F-15’s beyond-visual-range AIM-7 Sparrows, Syrian fighters could find themselves engaged without ever seeing their opponents. Additionally, the fact that Israel possessed AIM-9 Sidewinders with all-aspect targeting capabilities (i.e. not having to shoot an enemy from their rear quarter) meant many Syrian MiGs were essentially shot in the face at close range.

It was a slaughter, and a cutting-edge technological combat opera for the world to see. In just the first day of operations, lasting just a few hours, 17 of the 19 SAM sites in and around the Bekaa Valley were obliterated and 29 Syrian tactical aircraft were swatted from the sky. As a result, the battle was dubbed the “Bekaa Valley Turkey Shoot.”

Mission accomplished!

The incredibly lopsided and rapid victory proved the technological supremacy of western air combat over Soviet air defenses, and likely helped bring about the end of the Cold War. Lessons learned from the conflict also figured heavily into future American combat air operations. But above all, it proved the incredible utility of drones—not just for intelligence gathering in real time, but for their ability to assist in dismantling integrated air defense systems.

With this success in mind, Israeli weapons manufacturers started tooling with the idea of completely eliminating the hunter-killer kill chain concept. In other words, instead of unmanned aircraft provoking enemy radars to activate, then sending their location to command and control who then vectors in fighters to engage the radars with expensive anti-radiation missiles and other precision guided munitions, just have the drone do it all autonomously.

This was realized to a certain degree with existing drones that were modified for the mission in the years following the Bekaa Valley Turkey Shoot, but by the 1990s, a small and stealthy “loitering munition” was being fielded just for this purpose—the IAI Harpy.

The IAI Harpy on display at the Paris Air Show., Jastrow/wikicommons

The IAI Harpy on display at the Paris Air Show., Jastrow/wikicommons

The Harpy was relatively tiny, with a wingspan of just under seven feet and packing a 38-hp rotary engine. But what it lacked in size the little flying-wing drone made up for in punching power, packing a 70-hp high-explosive warhead. On its nose was its most critical piece of equipment, a seeker head capable of detecting and homing in on certain radar frequencies.

The idea was that a single truck could carry and launch dozens of Harpys to act as both bait and hook, flying to their predetermined target area where they would wait for enemy radars to come online. If that were to occur, the Harpy would fly right at the emitter, blowing itself up on arrival and taking the radar system with it.

It was an ingenious and cost-effective weapon system, albeit a one-trick-pony and more of a fire-and-forget SEAD missile than a reusable unmanned aircraft with a propensity toward suicide. Still, the Harpy has been an export success, with India, Turkey, China, Chile, and South Korea buying the system in quantity.

In the late 1990s, Israel began working on a follow-on to the Harpy. It would be a larger design that could be reconfigured for multiple uses, including attacking radars, providing both electronic and electro-optical intelligence, attacking targets of opportunity on the ground (say, vehicles). Plus, it could even be outfitted to come back home and be reused again.

Harop, with its folding wings, can be launched from a truck- or ship-mounted canister, or configured for air-launch. Once in the air, it can be operated by man-in-the-loop control or it can go about its mission totally autonomously. Either way, it can put its warhead to use, using its camera system and operator to track and engage moving targets or its radiation-seeker to sniff out and attack radar sites on its own. It can even be equipped for both missions at the same time, so that if a radar site were to go offline after a Harpy detected it, it can fly to its location and use electro-optical targeting to locate and kill it.

A huge difference between Harop and the Harpy is range and loitering time, with the modern iteration packing about double that of its simpler predecessor, or about 600 miles or six hours. That, plus the fact that it can be equipped to return home autonomously and land once its fuel runs low.

The Harop being launched from a canister., IAI

Basically, the Harop—which has the radar signature of a small bird and virtually no infrared signature whatsoever—offers an inexpensive solution for many unmanned missions in a small, transportable, and optionally reusable package. You can imagine that if you are the enemy, having dozens or even hundreds of these things roaming your countryside during a time of conflict would be pretty terrifying.

In the suppression of enemy air defenses role, you can also imagine that just having a swarm of Harops decend into the area of operations before a major set of airstrikes would keep enemy radar operators from turning on their systems at all. In this case, the Harop accomplishes its mission without even having to destroy itself in the process.

The Harop, like its progenitor, is already an export success, with India and Azerbaijan purchasing the system. In fact, it was put to use with devastating results by the Azeris just last spring, during fighting with the Armenians. The attack drone supposedly hit a bus full of soldiers, killing half a dozen of them in the process, and destroying the bus.

In many ways, Israel is far ahead of even the US when it comes to easily deployable “loitering attack munitions.” The American-made AeroVironment Switchblade, which is a small, man-portable loitering unmanned aircraft with attack capabilities, is in a whole different class than the far more advanced and strategically relevant Harop—or even the Harpy for that matter.

In fact, Israel has its own version of this system, the ROTEM, and they even have another, larger system, the Green Dragon, that is also forward-deployed with troops, but with more capabilities and endurance.

The truth is that all indicators point to a future where suicidal drones are the norm, not the exception. As such, a bull market is emerging around the concept. Even American domestic law enforcement has crossed over the robotic killer line.

What’s really exciting—or terrifying, depending on how you look at it—is just what the Harop could be capable of if a large quantity of them were networked together as swarm. Using electronic and kinetic attacks, they could wreak havoc on an enemy’s integrated air defense system in a cooperative fashion. Projects like DARPA’s Gremlins aim to accomplish just that, and do it via airborne launch and recovery—although this is likely just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what is actually out there in the classified world.

An artist rendering of DARPA’s Gremlins project. , DARPA

In the meantime, Israel’s Harop will reign supreme as the most versatile suicide drone on the planet, and one that has already been used effectively in combat.

Source: thedrive.com