Cats are famous for their independent and aloof nature, but a new study has revealed the way to the heart of even the most standoffish feline.

Scientists from the Paris Nanterre University sat in a ‘cat cafe’, where kitties roam freely and can approach customers, to test out different ways of winning them over.

They found that cats responded most quickly to human strangers when they offered vocal and visual cues together, like calling their name while reaching out their hand.

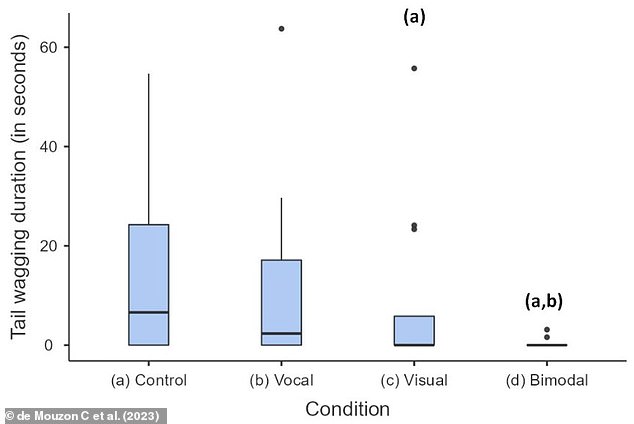

But when the human ignored the animals completely, they were more likely to wag their tail – a sign of frustration or agitation.

The researchers hope their findings will improve the quality of human-cat relationships and cat welfare.

Scientists from the Paris Nanterre University found that cats responded most quickly to human strangers when they offered vocal and visual cues together

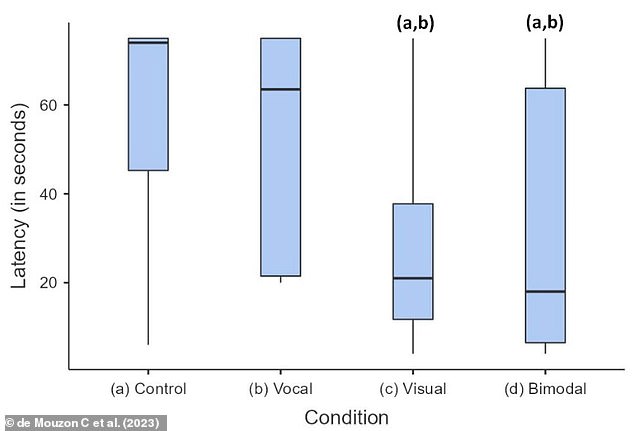

Cats responded most quickly to human strangers when they offered vocal and visual cues together, like calling their name while reaching out their hand. Pictured: Time taken for cats to approach the experimenter according to each testing condition

‘People should be encouraged to use appropriate visual communicative cues when engaging interactions with cats, especially with unknown individuals,’ the authors wrote.

WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO ATTRACT A CAT?

The results show that cats approach strangers much more quickly when they provided a visual or both a visual and vocal signal simultaneously.

‘A short latency of approach is thought to reflect higher attraction,’ the authors wrote.

Previous research has found that trained dogs do not respond as well to vocal signals from unfamiliar people as they do from familiar.

The authors suggest that this could be the same for cats.

Cats are known to have developed the ability to interpret and respond to human signals through their domestication.

Recent studies have found that they can recognise their owner’s voice when they are talking to them directly, and also view a slow blink as a smile.

However, according to the authors of the new work, research into human-to-cat interactions is currently limited.

For their study, published in Animals, the team wanted to find out how sensitive cats are to human cues, which ones they are most receptive to and how they respond.

They recruited 12 cats for the study, who had lived in one of two cat cafes in Bordeaux and Toulouse in France for at least three years.

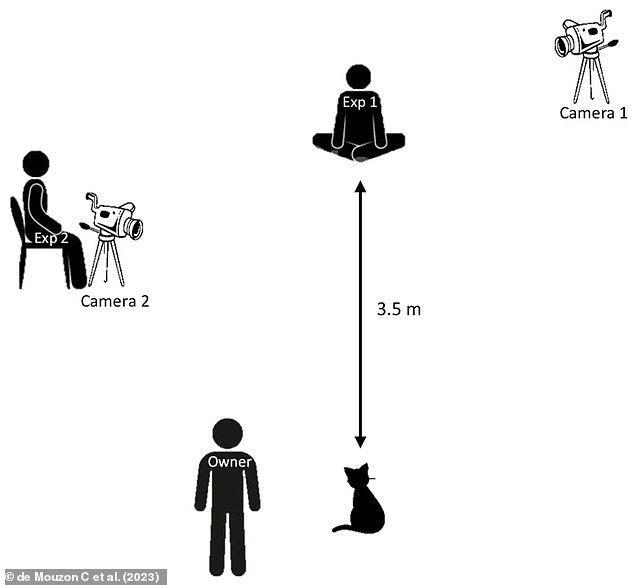

One at a time, the cats were led into a quiet room with their owner, where a researcher was waiting who it had never met before.

After 10 seconds, the researcher would do one of four things; offer a visual signal, a vocal signal, both a visual and vocal signal simultaneously (bimodal) or no signal at all.

Examples of visual signals were extending their hand and slow blinking, while examples of vocal signals were calling the cat’s name or making a ‘pff pff’ sound, which is widely used by French people to call cats.

The time it took for the cat to come within four inches (10 cm) of the researcher was recorded, as well as how they responded, like by vocalising, blinking or wagging their tail.

One at a time, the cats were led into a quiet room with their owner, where a researcher was waiting who it had never met before. After ten seconds, the researcher would do one of four things; offer a visual signal, a vocal signal, both a visual and vocal signal simultaneously (bimodal) or no signal at all. Pictured: Experimental setup

Cats wagged their tails much more when they were not given a signal than when they were given a visual or bimodal signal. Pictured: Tail wagging duration with each testing condition

After analysing the results, it was found that cats approached the researcher much more quickly when they provided a visual or bimodal signal.

‘A short latency of approach is thought to reflect higher attraction,’ the authors wrote.

They say that the vocal communication by itself may not have been attractive because cats are not accustomed to being called without the human making eye contact.

Additionally, of all the different responses the cats gave, only tail wagging was found to be significantly affected by the type of human communication signal given.

They wagged their tails much more when they were not given a signal than when they were given a visual or bimodal signal.

‘Lateral tail movements tend to occur when cats are facing a frustrating situation,’ the authors wrote.

‘Therefore our data suggest that being in a room with an unfamiliar human ignoring them might be uncomfortable for cats, if not frustrating.’

The researchers conclude that cats display a preference for visual and bimodal cues expressed by strangers. They say this is evidence that cats have developed specific ways of communicating with humans through their domestication, which have proved effective and beneficial to the species

There was also more wagging in response to the vocal cue than the bimodal, suggesting this was more frustrating for them.

Lead author Dr Charlotte de Mouzon told Gizmodo that the cat may be especially stressed because they had previously played with humans in that very room, but now they were ignoring them.

They conclude that cats display a preference for visual and bimodal cues expressed by strangers.

They say this is evidence that cats have developed specific ways of communicating with humans through their domestication, which have proved effective and beneficial to the species.

Previous research has found that trained dogs do not respond as well to vocal signals from unfamiliar people as they do from familiar.

The authors suggest that this could be the same for cats, and would explain why they were not so attracted by the vocal cues alone from the unfamiliar researcher.

‘Results arising from the present study may serve as a basis for practical recommendations to navigate the codes of human–cat interactions,’ they wrote.