The odds of suffering an attack from bears are slim. Odds of surviving one can suddenly matter more.

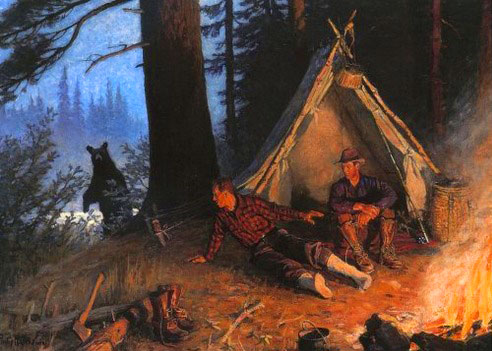

Fates seemed bent on bringing Joe to grief. No one could say why. The slightly-built, 65-year-old herder was reliable and industrious. He’d earned and saved enough tending Montana sheep to buy a small farm in the Midwest. A retirement home.

The bear came early in the fall of 1947. Joe knew these predators well. He’d shot some. When a ruckus among the sheep brought him from his wagon one night, he spied a black form and fired. The .30-40 bullet killed the best dog he’d ever owned. That week, lightning struck his Minnesota farm, reducing the barn to ashes.

Josif Chincisian began dispersing the little money he had to friends, insisting he wouldn’t need it.

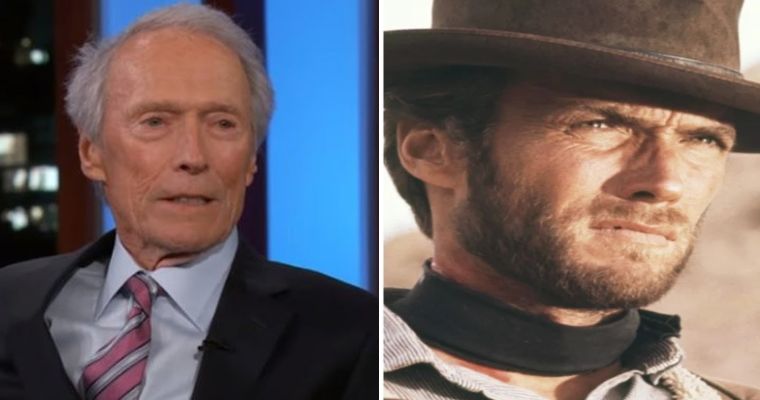

HY Watson

After another sheep was lost to a bear, the flock was moved to less remote pasture, Joe parking his wagon on a rise above a willow-lined creek.

When bleating sheep again awoke the herder, he grabbed a light, his cane and the Krag. Leaving his dog inside, he probed the darkness around the wagon, then followed the trail down toward the creek.

Before he could aim his rifle the bear was on him.

Searchers would find the two dead sheep easily, a flashlight and cane nearby. Blood would lead them into the willows, to leaves the beast had piled on Joe, and a bone fragment torn from his skull. His Krag would be found, fired, bolt open and bloodied….

Struggling up out of his grave that night, Josif had staggered to a derelict, doorless cabin a short distance from the creek. He’d rested, then made the excruciating climb back to his wagon. Around noon the next day, scalp and ear stiffening over his face, he grimly set out for the Heydweiller ranch, a mile and a half away. Riding for cattle, Henry Heydweiller found him collapsed on the trail.

Joe would not regain consciousness. Ten days later in a Great Falls hospital, despite ministrations that included brain surgery, the Rumanian sheepherder died.

Dogs lost the bear’s trail. Another herder moved the flock to corrals nearer the ranch and bunked in an adjacent shack. One night he heard a commotion outside but obeyed orders not to investigate. Dawn showed a bear had climbed into the corral, killed a ewe and hauled her back over the fence, dragging her within yards of the shack before scraping leaves over the carcass in nearby aspens. Eerily, the beast then bedded beside the shack, as if waiting. It left before daybreak without touching its kill.

The grizzly that had struck down Josif Chincisian that September night in 1947 was never found.

Several years ago, hunting elk after a Montana snow, I came upon fresh grizzly prints. We were sharing the mountain. When next day new tracks appeared above timber in scraggly pines that trimmed odds of a chance meeting, I followed them. The trail led up a steep pitch, then, abruptly, ended. A slide caught my eye. It shot down through the pines, a long toboggan run, the snow dished by the bear’s ample rump. I descended, caught the trail at run’s end and followed it back up to a bed.

Bears know how to have fun, and when to call it a day.

One autumn evening in Oregon, a friend took me in his Cessna 180 to a remote grass strip above Hells Canyon. Snugging the airplane, we separated to look for elk along the rims. A bumper crop of ripe elderberries colored the canyon heads. During that hour before dark, I saw nine black bears, most within a few yards. They showed neither aggression nor alarm, ignoring me or slipping away into thicker places.

Bears seem to know what you’re about.

Watch cubs wrestle or one hang from splayed feet on the rim of a barrel to reach the bait inside, and you gotta think “cute.” A bear slapping water to catch salmon a blink quicker is entertaining. Ditto one scratching its back on bark or sprawled in the sticky remains of a stolen melon.

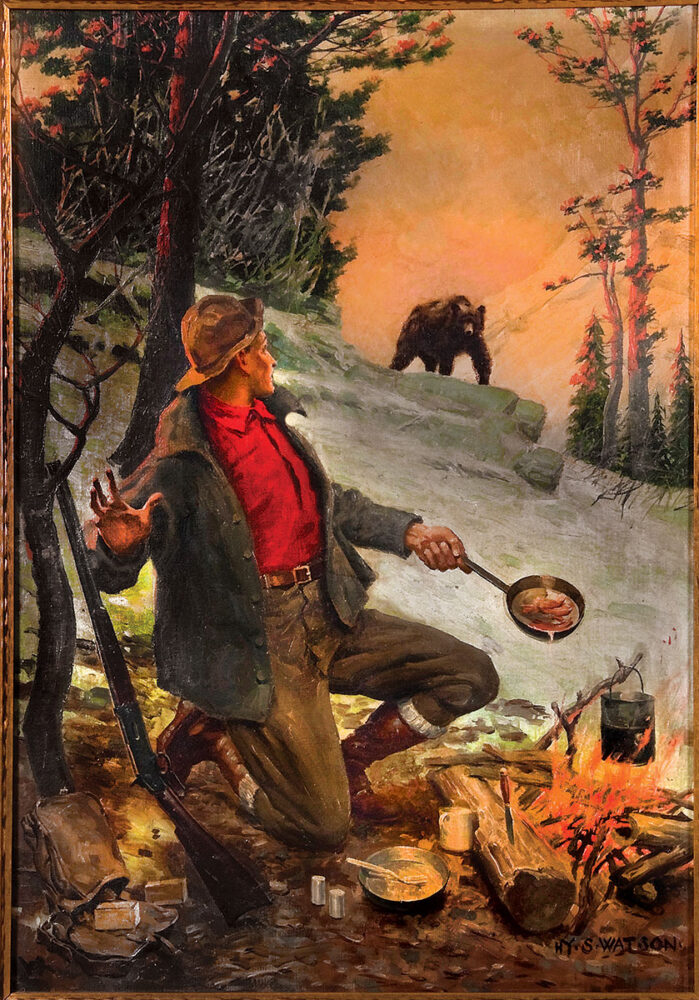

After Teddy Roosevelt spared a bear on a 1902 hunt, this Berryman cartoon gave rise to “teddy bear.”

To some people, the teddy bear defines these animals. It’s an unhelpful image whose debut in a Washington Post cartoon by Cliff Berryman followed a 1902 hunt by Teddy Roosevelt. The group’s dog handler, Holt Collier, was a slave who’d served as the Confederacy’s only Mississippi-born black soldier. He roped a bear that had sought refuge in a lake and hauled it ashore for Roosevelt to shoot. T.R.’s refusal to kill that bear inspired the cartoon, and an enduring, endearing, if mythical creature.

Bears remind us of ourselves, or of what we might be, spared our cultural cage. They’ve no sense of propriety or shame. Protocol is beyond them. Egalitarian in nature, but with a free-enterprise view of food, they bridle only at threats to their young or their dinner.

Bears do kill people. Just a week ago at this writing, Austin Pfeiffer and his hunting partner shot a moose in Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. After gutting the beast, the two returned to their tent. Butchering and packing would wait until daylight.

Come morning, Pfeiffer tended to the moose while his partner ferried meat. Returning for another load, the man was accosted by a bear. His rifle fire turned it. One of several shots may have struck home.

At the moose, he found Pfeiffer dead, apparently surprised by a bear. A Tok air service eventually caught repeated calls for assistance.

Pfeiffer, from Mansfield, OH, became the first person on record killed by a bear in Wrangell-St. Elias since the 13-million-acre park was established in 1980. Just 22, he’d been married for less than two years. The bear that killed him was never found. It’s unknown whether Pfeiffer’s partner encountered the same bear, or whether his shots took effect.

“In bear country, you must be ready to meet bears,” Al Johnson told me. “And when you see one, you have to be smart. I wasn’t.” In the fall of 1973, the Alaska Fish & Game biologist was photographing moose in Mt. McKinley National Park.

“Shot once, used knife, grappled, tumbled over cliff.”

From the road, he spied a grizzly sow with three cubs. Grabbing cameras and lenses, Al followed the bears on foot. Maintaining a 100-yard safety buffer, he shot with a 1000mm lens until fading light forced a shorter lens. A predator call, he knew, might coax the bears into its limited reach. “I climbed 15 feet up a tree and squalled.” The sow paid no attention at first. But when he stopped calling, she approached at a brisk walk, cubs trailing.

She was inside 50 yards when Johnson shouted to warn her off. She came on, swatting his pack as she passed his tree. Then one of her cubs looked up and bawled.

“I felt the tree shake violently,” Al recalled. “then saw her head and shoulders at my feet.” While grizzlies can’t match black bears as climbers, they’re not earth-bound. The sow grabbed Johnson’s boot and tore him from the tree.

Dashed to the ground, Al turned on his stomach and clasped the back of his neck, enduring deep bites to his arms as he shielded his head. “Her teeth scraped my skull. Then she left.”

Johnson was fortunate. Soon after he staggered 300 yards to a lightly traveled road, a medically trained Park employee happened by. Before surgery in Fairbanks, Johnson got four pints of blood.

This Canadian hunter’s powerful iron-sighted rifle is insurance against surprising a bear in the alders.

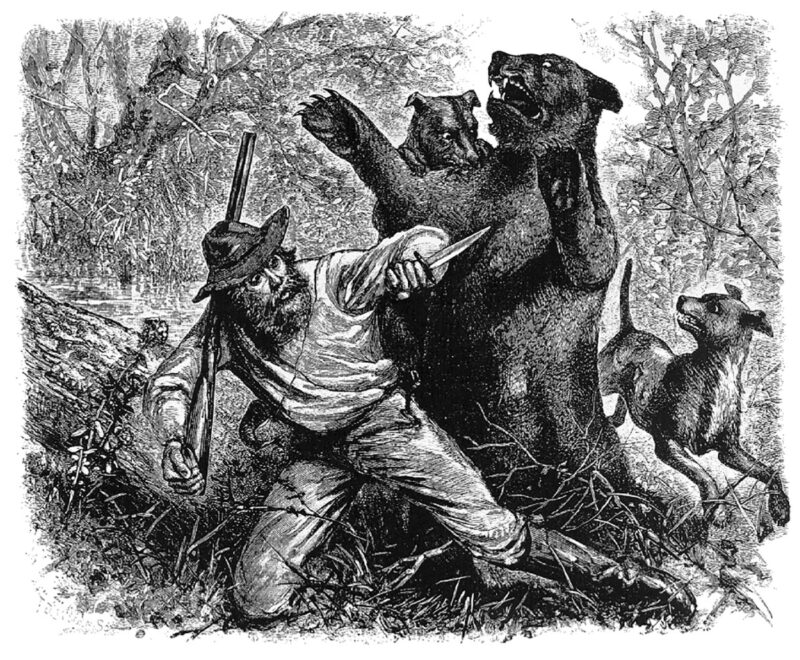

“Shot once, used knife, grappled, tumbled over cliff.” You had to be tough to deal with Alaska’s bears in 1900. Before airplanes swarmed lakes and gravel bars, few of these beasts had seen a human. The pithy record of that tussle indicated the bear “mistook man for sheep or hunger.” So wrote Larry Kanuit who, years later, earned a few liras with books on bear attacks.

Early assaults could be rigorous even if the bear didn’t press its advantage: “Archie was mauled, played dead. Mongrel dog intervened. Bear chased dog. Bear left. Partners sewed him up with an old sail needle and snowshoe lacing.”

In a 1989 book, Kanuit compiled a list of 170-odd bear maulings recorded in Alaska since 1900. Only 19 were attributed to black bears. Polar bears did not make that roster, so the remaining injuries and fatalities were caused by grizzly and brown bears. That list will surely grow.

In September 1988, Lawrence, “L.W.” Jones was hunting in Alaska’s Yentna drainage when the alders scant feet away “came to life.” A grizzly was on him so fast it slapped the barrel of his rifle aside before he could fire. In the maelstrom defining the next seconds, Jones jammed the Weatherby’s muzzle into the bear’s mouth. The animal bit it, wrenched it away and lunged before Jones could reach the .44 Magnum in his shoulder holster. Its teeth tore the holster; the Redhawk flew out of reach. “The bear then bit through my left shoulder, picked me up, shook me [threw me down and] began mauling my head….” His ear “wound up in three places.”

Become the Bear (Imminent Doom) by Sally Maxwell

Snatching him up again, by the thigh, the bear slammed the hapless hunter to ground and, to turn him over, hooked claws into his stomach, ripping it open. Still face-down, Jones lay still. When he could no longer hear the beast breathing, he struggled to hands and knees, donned his ball cap “to hold my scalp and ear,” and used his mangled shoulder holster as a tourniquet. He picked up his rifle and limped to camp as fast as wounds permitted. Four hours of surgery followed the boat trip to Skwentna.

Jones could offer no reason for the attack.

A cause commonly becomes evident after the fact. Often, it’s the presence of a carcass or cubs. In 1981 Fred Roberts answered a newspaper ad to work as an assistant hunting guide on Kodiak Island. The last week of October the Montanan flew to camp to join a senior guide and a client. A couple of days later he was called upon to pack out a deer. Approaching the carcass in alders, he heard a footfall. Looking up, he saw a bear “coming at me flat out.” She was on him instantly, hooking his back and clamping her jaws on his right arm. “She lifted me and slammed me onto the ground.”

After repeated tosses, Fred landed in a depression where he could curl up to shield his vitals. The bear bit his pack, then tore into his head above the pack’s extension. That extension may have saved him. His face was minced, one eye “hanging loose.” Peeking as the bear left, Fred saw two cubs. When certain the animals were gone, he crawled to where his companions could find him. Two and a half excruciating hours later, the trio reached the boat. Air rescue came late that day.

Watchful Bear by Bob Kuhn

Since 1980, grizzly bear populations have increased in much of their lower-48 range. As fall brings shorter, cooler days, bears ramp up their search for food. Hunting seasons put people in their path.

Two years ago in the northern Rockies, a hunter was injured and his guide killed by a grizzly that blasted from cover as they field-dressed an elk. Short miles away, one of my hunting companions barely had time to fire in front of a bear that charged after he’d walked by. It dashed past him, evidently with a sudden change of heart. Another hunter, retrieving at dawn an elk he’d shot the previous evening, found a grizzly had eaten its back and ribs, then buried the quarters. Grizzly traffic in the area was so heavy, paw prints on pack trails had erased the cuts of horse and mule shoes.

For decades, outfitter Ron Dube hosted hunters in elk camps east of Yellowstone. He never had to kill a bear. “I’ve seen dozens of grizzlies,” he told me, “some up close. A young male followed the scent of food into a spike camp where I was alone, frying supper. I yelled and got in his face, threatening to bite his head off if he didn’t leave. He did.” Dube recalled only once being alarmed by a bear. “A client and I came upon a big grizzly pacing near a carcass. Though unaware of us, he growled and bristled, clearly an agitated bear. We backed off and hunted away from him.”

“Stay alert to avoid grizzlies. If you’re surprised, back off. A loud noise and a bluffing posture can salvage the situation.

Avoiding contact is always a good idea. On a late hunt in southern Montana, I descended in deep snow after a bloodless day and rested at the foot of a slide. Slipping my pack off under a pine, I spied an elk carcass in timber’s shadow nearby. Minutes later, snow on the slope above burst in a bright, backlit cloud. Silvered coat rippling, an adult grizzly catapulted downhill, enveloped by sparkling powder. The great beast passed me and skidded to a halt at the elk.

I hugged the pine, starkly alone in the small glade. The bear was now batting the skull about. An invisible hand reeled it my way. The wind will give me up! Clutching my rifle, I wished the bear into the forest. He met my scent at 19 yards and stiffened. Tense seconds later he loped into the conifers. I put the pine between us and walked quickly away, past the elk. His elk.

Running from a bear is foolish, as it can trigger a predator-prey response. Also, bears can sprint at more than 40 mph. Best advice for hunters coming upon a carcass—back off. A bear may be watching its prize from cover. Approaching game you’ve shot but had to trail, walk slowly, talk loudly. Still, like meeting someone to whom you owe an apology, you can by chance bump into a bear.

Alaska guide Morris talifson shot this 11-foot brown bear in 1949. Big Bears aren’t necessarily hostile.

In the summer of 1957, Jack Turner and wife Trudy homesteaded on British Columbia’s Atnarko River. Fed by melt from snowfields in peaks to the south, the Atnarko is a conduit for spawning salmon. September sockeye and humpback runs bring grizzlies off the slopes. Jack had once counted “ten adult grizzlies and five cubs along a seven-mile stretch of the Atnarko, all in one day” and figured as many as a dozen bears fished near the house until coho runs ended in December.

One day Trudy surprised a sow grizzly and two cubs tearing the garden apart. Rows of carefully tended vegetables lay stripped and mashed into the earth. Killing the trio was distasteful, but the Turners’ had to salvage what was left. Trudy’s parents, the only neighbors within 20 miles, suggested killing one cub. The sow would likely take the other and leave.

That plan fell apart when, after tracking the trio, Turner’s bullet struck both cubs and brought the sow on. “She came for me in a rush, businesslike and deadly.” She fell mere feet away.

“Most bear attacks are launched by sows protecting cubs or by bears guarding or claiming kills.

While bears with cubs proved an enduring hazard, a lone male would give Jack his worst scare.

Early one morning in 1965, he left the house to repair a fence. Ax in hand, his .30-30 slung from a cord across his back, he hiked up the Atnarko. Where the trail bent in a tiny glade, he met “the biggest grizzly I’d ever laid eyes on” at 13 steps. Instantly, “he was on the way, no warning growl or popping of teeth.” Turner dropped the ax and whipped the carbine from his back. In one motion he levered a round into the barrel and flipped up the sight. The bear was almost on him when a bullet destroyed its brain.

What accounted for that charge? “I’ll never know,” said Turner, who could find no evidence the bear had been feeding on flesh anywhere in the vicinity.

That grizzly proved exceptional as to size as well as behavior. Measured for Boone and Crockett score, the skull matched that of the world record bear taken in 1954. Both now rank in 11th place.

As the grizzly’s reputation engenders fear, the ubiquitous black bear cultivates tolerance. A clever beast, it is secretive in the wild but quickly acclimates to humans. It is seldom menacing. Black bears get a pass as clowns—if in gardens, apiaries and tree nurseries they soon wear out any welcome.

I was conscious of my flesh being torn, teeth against bone…canines crunching my skull.

Oddly, a black bear can pose a significant threat. Records of black bear attacks indicate a number of victims were stalked, while most grizzly assaults are attributed to bears shielding their cubs or claiming a carcass. Bears treating people as prey are exceedingly dangerous, as 1) they come cat-quiet, not wanting to chase you off but to kill you, and 2) prevailing, they won’t leave you for dead; they’ll eat you.

A study published in 1980 by Canadian journalist Mike Cramond included records of more than 250 bear attacks from 1929. He conceded the data is incomplete (gaps mainly from parks). But it showed grizzlies and blacks in a close finish as regards attack totals: 72 by wild black bears, 80 by wild grizzlies. Human fatalities: 12 and 14. Half the people killed by both species had been fed upon.

I was conscious of my flesh being torn, teeth against bone…canines crunching my skull.

Yes, Cramond’s Canada-based findings as to the percentages of black and grizzly bears in attack totals are at odds with Larry Kanuit’s Alaska list. There’s some logic to that disparity. But data is of little comfort to people accosted by bears.

Early on August 12, 1977, chopper pilot Ed Spencer delivered Cynthia Dusel-Bacon to a ridge 60 miles out of Fairbanks. She wore a rucksack with lunch, a rock hammer and, in an outside pocket, a radio. Pick-up would be eight miles down-country. Camp’s radio, tended by Ed’s wife, was 80 miles away.

Though her team often split to work alone, 30-year-old Cynthia carried no firearm as she mapped Alaska’s Yukon-Tanana uplands for the U.S. Geological Survey. “Our supervisor said guns added more danger than they might prevent.” That day, a trail through the brush made walking easy.

When Cynthia stopped to chip a shard from an outcrop, “a sudden crash in the bush startled me. I looked up and saw a black bear rise just 10 feet away.” She yelled, waving her arms. Instead of leaving, the bear came toward her, stealthily. Then it rushed her. She endured “a staggering blow” and fell face-down. Though she willed herself not to move, the bear continued mauling her, biting deep into her right shoulder and shaking her. When it paused, Cynthia reached for her radio. But she still wore her pack and couldn’t access the pocket. That movement brought another attack. “I was conscious of my flesh being torn, teeth against bone…canines crunching on my skull.”

Blacks attack. And devour.

The beast grabbed Cynthia’s arm and pulled her into the brush. Periodically it licked at the blood from her wounds. After “almost a half-hour,” Cynthia got her left hand to the now-torn pack pocket and keyed the radio. “Ed! Come quick! I’m being eaten by a bear!” The animal pounced again.

Spencer caught the message and took off immediately. But from the chopper he couldn’t see the prostrate woman in the brush. When he did spot her, he had to fetch help to move her. Cynthia would lose both arms in surgery. Her strong will and positive attitude would speed her recovery.

Young, healthy animals like the bear that mauled Cynthia, and another black bear that killed three boys fishing an Ontario river in 1978, can be as dangerous as aging loners soured on people. Scarcity of natural forage can produce problem bears—so too a flush of human traffic where bears have congregated. Hostile encounters hinge on conditions that change seasonally and year to year. An Ontario wildlife agent noted that in 1974 he had to destroy 51 black bears. “In ’77 I killed 17, in ’78 just one.”

“In bear country, you must be ready to meet bears.”

Backing away slowly from a bear to show you’re not a threat is generally thought the best way to avoid an attack. Scaring a bear off by shouting or making yourself appear big can work if you’re in home territory, not surprising the bear on its turf. A charging bear may stop or swerve if you stand your ground. Playing dead can halt a mauling; but if the assault is predatory, it avails nothing. Fighting a bear pressing an attack makes sense if you know it’s predatory (hard to tell) or if there’s a weapon at hand.

Carrying handguns in bear country is commonly discouraged and not everywhere permitted, lest hunters use them prematurely, shooting animals that pose no clear threat. There’s something to this. Bears can “false charge” or change their mind mid-stride. Once, surprised by a sow with a cub, a friend hastily fired his revolver in front of her. She jetted by on one side, the cub on the other. He can’t say if his bullet turned her. Given time for one shot, should you charitably send it to ground?

Bear spray has proven a viable deterrent in bear attacks. It is prohibited in most aircraft, however. And like a bullet, spray must be aimed. A grizzly that recently killed a hunting guide had spray residue on its chest when rangers shot it. Spray is for the face. A spray can that is not instantly accessible or deftly handled is useless. An advantage of spray over bullets: It’s not lethal; you can use it without knowing if you must. The best protection against bears is still vigilance and clear thinking.

Bears That Act Human

Bears more accustomed to people can become like them, their wild innocence replaced by a surly, self-serving impudence that tests your charity. Once in rural California, I booked a room in a rustic lodge on the rim of a lake. Walking the grounds at dusk, I saw people clustered on the back porch. A black bear was having its way with a prostrate garbage can at the kitchen door. As onlookers edged closer in an arc, I observed aloud that bears are very fast, and belligerent when cornered. The crowd halted. Doing the bear a favor, I shooed it from the can. It descended the stairs with a snarl as I closed the distance to a few feet. Then it turned, teeth bared. Though a young bear and not much over 100 pounds, it looked ready to shred me for a cold slice of used pizza. I tried to look meaner than the bear felt, and must have succeeded.