Adaptive engine technology and other improvements could significantly boost capability but would come at a cost.

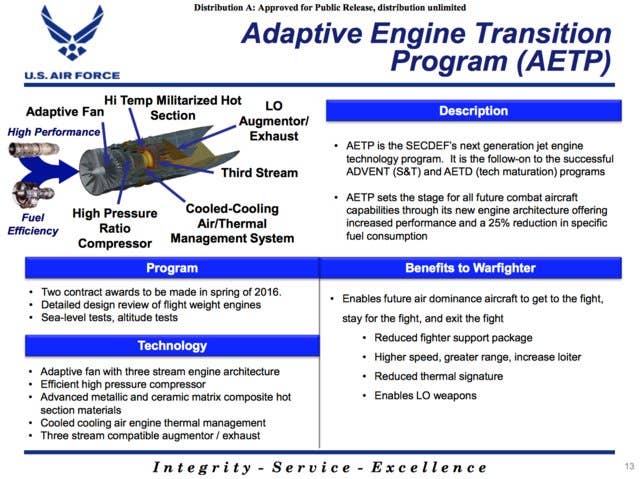

ongress could be able to require the U.S. military to prepare a pair of studies about what it would take to put new engines into current and future F-35 stealth jets later in this decade. There is an entirely new powerplant under development under the Adaptive Engine Transition Program, or AETP, with multiple prototypes being tested already. The hope is that the AETP engine or some other alternative would bring a significant performance boost to all three variants of the F-35, as well as offer improved efficiencies.

Writing in Air Force Magazine yesterday, John Tirpak pointed to the wording in the most recent draft of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the 2022 Fiscal Year. The bill, which has still yet to pass in the Senate, would require the Secretary of the Air Force, working with Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, to lay out a plan for adding AETP engines to F-35A conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) aircraft starting no later than 2027. The Secretary of the Navy, together with the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, would produce a similar, but separate plan for adding an “advanced propulsion system” – which could be the final AETP design or an enhanced version of the existing Pratt and Whitney F135 – to F-35B short take-off and vertical-landing (STOVL) and F-35C carrier-based variants, again starting in 2027 at the latest.

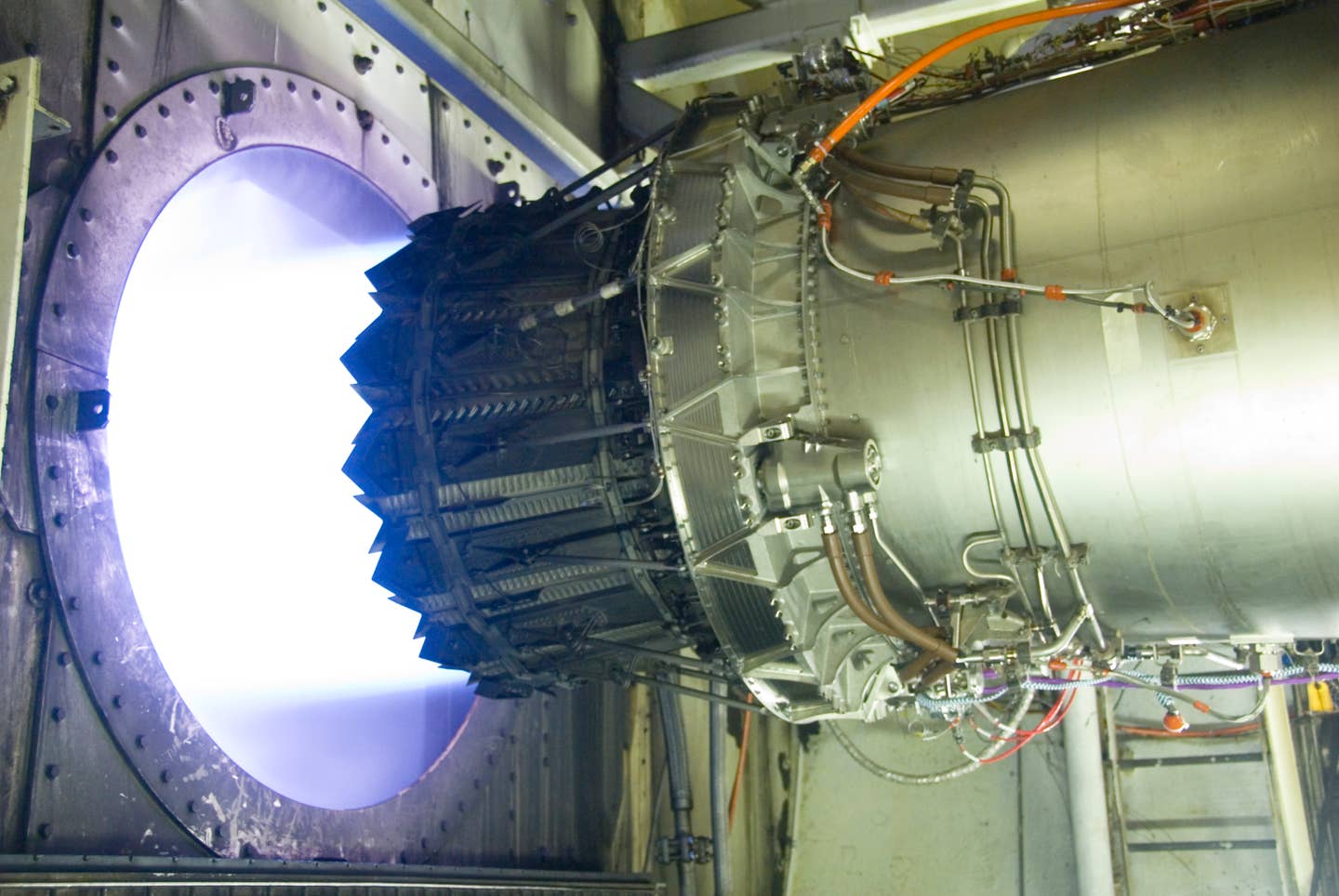

The business end of the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine powering a U.S. Air Force F-35A., U.S. Air Force

The business end of the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine powering a U.S. Air Force F-35A., U.S. Air Force

In both cases, the outlined “competitive acquisition strategy” would cover adding AETP engines to existing and new production aircraft. Both reports would have to be submitted within two weeks of the delivery of President Joe Biden’s proposed the Fiscal Year 2023 budget request to Congress.

The costs involved in integrating any new powerplants into all three variants of F-35 could be considerable.

For the Air Force in particular, which is the largest current U.S. operator of Joint Strike Fighters of any type, there is certainly a question about whether the service has the means to give all of its existing and future jets entirely new AETP engines. There are already separate concerns about the expenses involved in sustaining existing F-35As, as well as bringing them to the latest Block 4 standard that includes enhanced radar and electronic warfare capabilities, plus the ability to carry new weapons.

In the past, Lt. Gen. Eric T. Fick, the Program Executive Officer for the F-35 Joint Program Office, has said that the Air Force would have to cover the development and production costs of integrating the AETP engine in the F-35A.

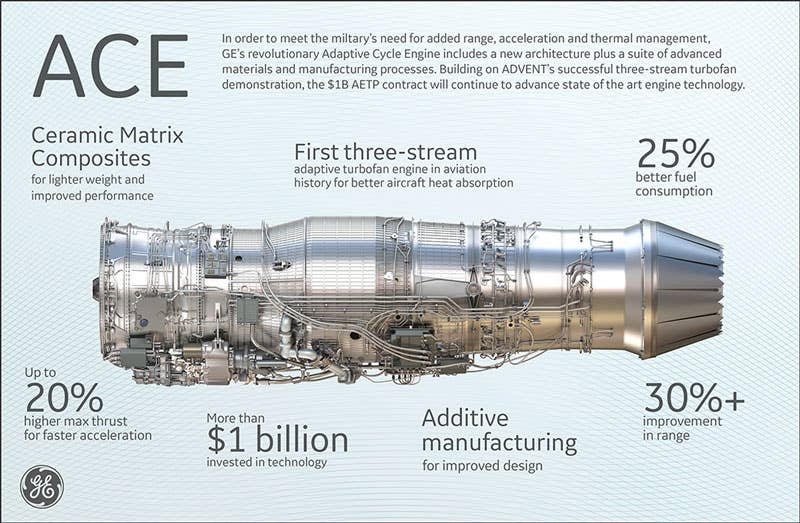

Right now, prototypes of two options for the AETP, the General Electric XA100 and Pratt & Whitney XA101, are being tested. Both of these powerplants are expected to increase the range of the jet by around 30 percent, and persistence by some 40 percent, achieved by cutting fuel burn by around a quarter. Currently, the F-35A has an unrefueled range in the region of 1,350 miles, which would be increased to around 1,800 miles with the new engine. The acceleration would also be improved with the new engine installed.

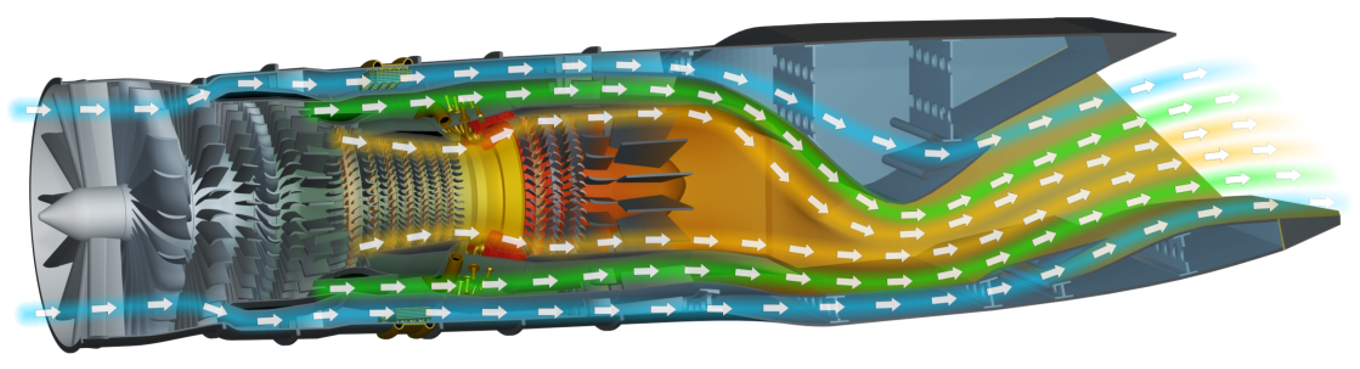

The ‘Adaptive’ part of the name refers to the fact that these new engines combine the fuel economy of the kinds of turbofans used in new-generation airliners with the high-pressure compression normally found in fighter engines. By introducing a third stream of air, this can be dynamically modulated between the engine’s core and the bypass stream, to provide increased thrust during combat conditions and increased fuel efficiency during cruise conditions.

Schematic illustration of an Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) design., U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force

The XA100 from GE., General Electric

In particular, giving the F-35A longer legs is something that would be of huge benefit to the Air Force, as it looks toward the likelihood of the next major conflict taking place in the Asia Pacific theater, where the Lightning II’s limited range would be a major concern. As the service plans for its next fighter, an increased range has already been earmarked as a ‘must-have’ feature.

Not only would a longer-range F-35A be more suitable to operations in the Asia Pacific region, but it would also reduce dependency on aerial tankers. The availability of sufficient inflight refueling aircraft has always been a key factor for air combat planners. More recently, however, the survivability of those same tankers has become a real worry, with interest in more survivable tankers, achieved through low observability or through other means.

An F-35A approaches a KC-135 Stratotanker during aerial refueling near Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. , U.S. Air Force/Master Sgt. John Nimmo

An F-35A approaches a KC-135 Stratotanker during aerial refueling near Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. , U.S. Air Force/Master Sgt. John Nimmo

As well as improving all-around capabilities, a new powerplant would address an ongoing problem with excessive wear to the heat-protective coating on the F-35A’s turbine rotor blades. Earlier this year it emerged that 46 of the jets were without functioning engines due to the issue. With the engine maintenance center facing a backlog on repair work, frontline F-35 fleets have been hit, and the Air Force’s fleet has suffered the most significant availability shortfall.

In the recent past, Air Force Chief of Staff General Charles Q. Brown Jr. has also noted that the F135 engines are “failing a little faster in certain areas,” as a result of heavy usage and regular deployments. While changes to maintenance are being looked at, Brown also suggested that one solution to the issue may simply be to use the F-35 less—hardly an ideal solution in the long term.

Two U.S. Air Force F-35As at an “undisclosed location” in the Middle East last year, demonstrating their ability to rapidly shift assets within the region to respond to emerging contingencies., U.S. Air Force

Two U.S. Air Force F-35As at an “undisclosed location” in the Middle East last year, demonstrating their ability to rapidly shift assets within the region to respond to emerging contingencies., U.S. Air Force

While the timeline for the new engine is bold, General Electric and Pratt & Whitney have told Air Force Magazine that the 2027 target date is achievable. The members of Congress who put together the most recent NDAA appear to be extremely supportive of the adaptive engine program, with the bill proposing to triple its funding in the 2022 Fiscal Year over what had originally been requested.

At the same time, while members of Congress are pushing for adding the AETP engine to the F-35A, the draft NDAA leaves open the possibility of going in a different direction with the F-35B and F-35C. The study for the F-35B and F-35C would include an “analysis of the impact on combat effectiveness and sustainment cost from increased thrust, fuel efficiency, and thermal capacity for each variant of the F-35, to include the improvements on acceleration, speed, range, and overall mission effectiveness, of each advanced propulsion system.” There is no specific mention of AETP.

The demands of the aircraft carrier operating environment for the F-35C and, above all, the swiveling nozzle and integrated lift engine for the STOVL F-35B mean the challenges of integrating a new engine are greater. Indeed, in the past, both General Electric and Pratt & Whitney have said their AETP designs are not compatible with the F-35B. With that in mind, the NDAA may be expecting the B-model to use the enhanced F135 engine, while the F-35C gets either the same or a version of the new AETP powerplant.

The Navy report is also to provide an assessment of how an advanced propulsion system could reduce aerial tanking requirements, and any “overall cost benefit” from “reduced acquisition and sustainment.”

Once the two reports are prepared, Congress will have a schedule “annotating pertinent milestones and yearly fiscal resource requirements for the implementation of such a strategy.” With an average price tag of $20 million for the current F135, it might be expected that the new engine will be substantially more than that.

Should Congress consider that the re-engining scheme is worth pursuing, it’s not clear what the next step would be. Early in the Joint Strike Fighter program, there were two engines, the F135 and General Electric/Rolls-Royce’s alternative F136, although the latter was dropped on cost grounds, somewhat controversially.

A General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136 engine is tested at maximum thrust conditions., Rick Goodfriend

A General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136 engine is tested at maximum thrust conditions., Rick Goodfriend

It could be that the Air Force has learned from that lesson and will decide that the XA100 and XA101 should both proceed to production, after which they can compete to win contracts, perhaps to power the F-35, or other platforms.

For the F-35, of course, the AETP could still prove to be ‘an engine too far.’ At that point, Pratt & Whitney would be well-positioned to pitch its improved F135 engine, which also promises improvements to thrust and efficiency, but which the company says would be much cheaper than AETP technology.

With a substantial production run ahead of it for both the U.S. Department of Defense and foreign customers, it makes sense for the Joint Strike Fighter’s powerplant to keep pace with technological developments in the same way that other aspects of the jet are enhanced via upgrades and new iterations. But whether the Air Force, let alone other operators can foot the bill for integrating this promising new engine technology into the already costly F-35 is currently questionable.

Source: thedrive.com