A deep trawl has brought up a potentially new species of a fish whose extreme mating methods include permanent physical fusion

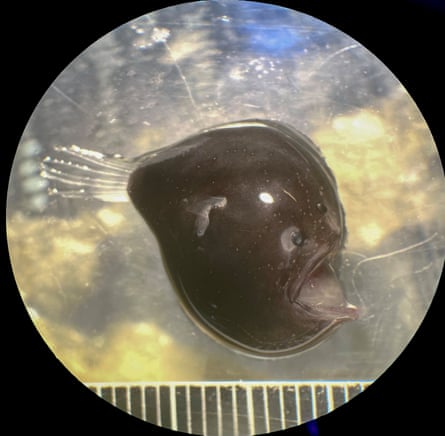

A juvenile female footballfish (possibly Himantolophus melanophus), a type of anglerfish. The white spots on the body are sensory organs that help the footballfish detect prey. Photograph: Chris Fletcher/NHM

“I sometimes describe anglerfish as looking like a satanic potato,” says James Maclaine, senior curator of fish at London’s Natural History Museum, who believes a new species of the fish may have been discovered.

Many anglerfish are globular and lumpy in shape. They have a long prong sprouting from their forehead with a glowing tip that lures prey into their enormous, tooth-filled jaws. If their appearance is curious, then the method of reproduction that some species have developed – known as sexual parasitism – is even more so.

A young female black seadevil anglerfish. Males of this species do not attach permanently to the female. Photograph: Chris Fletcher/NHM

Anglerfish reign supreme in the permanent darkness of the ocean’s midnight zone, between 1,000 and 4,000 metres down. There are at least 170 deep-sea anglerfish species. “No other vertebrate group comes close to anglerfish in terms of variety and number of forms at that depth,” says Maclaine.

The truth about the sex lives of anglerfish was discovered in 1925 by Charles Tate Regan, an ichthyologist at the Natural History Museum. When people saw smaller fish attached to larger anglerfish, they presumed they were juveniles stuck to their mothers. And when other specimens of these little fish were found on their own, they were thought to be a totally different family of anglerfish.

But in both cases they turned out to be diminutive males that belonged to families of anglerfish that had already been discovered.

In some species of anglerfish, including a very rare footballfish (Himantolophus melanolophus), the small male tracks down a female and bites on to her. When she releases her eggs, he fertilises them then swims off into the dark to search for another mate.

In other species – such as the stargazing seadevil (Ceratias uranoscopus) and the triplewart seadevil (Cryptopsaras couesii) – it’s a permanent arrangement. A male latches on to a female, their body tissues fuse and he never lets go. Only then does he grow a pair of testes and become sexually mature. “He will connect to her blood supply and feed off the nutrients in her blood like a little vampire,” says Maclaine. This extreme strategy of anglerfish mating was filmed for the first time in the wild in 2018.

A female anglerfish can collect several males. “The record that I’m aware of is eight,” says Maclaine. In some species, the males always fix in a similar place, usually near her rear where eggs are released. Others, including those seeking permanent attachment, clamp anywhere on the females including her head and even glowing lure. Sometimes, scientists find males fixed to a female of a different species. “I don’t know whether that’s just desperation or misidentification,” Maclaine says

An unidentified male anglerfish. Male anglerfish do not have a glowing lure on their heads but often have very large nostrils to help them detect a female. Photograph: Chris Fletcher/NHM

A 2020 study revealed that to adopt their parasitic mates, female anglerfish turn down – and even completely abandon – major parts of their immune system. By altering the genes involved in detecting foreign cells, including those producing antibodies, females don’t react to the hitchhiking males and rather accept them as part of their own body. “They still have some kind of immune system, but as to how that works, nobody knows,” says Maclaine.

A new species of anglerfish may have just been discovered. A black, golf-ball sized juvenile was brought up in a trawl net off Saint Helena in the mid-Atlantic on a recent expedition as part of the Blue Belt programme, which studies the waters around the UK’s Overseas Territories. Maclaine realised it was unusual because of its elaborate lure, like a minute bouquet of flowers. This feature is only known in footballfish. Just six specimens of footballfish have so far been found, so Maclaine’s catch may be one of those – or something new, he says.

As soon as the research ship returns to the UK in a couple of months and Maclaine has access to the specimen, he plans to make detailed drawings of its lure, unfurling the intricate tendrils that will have been scrunched up. For this kind of identification, drawings are more useful than photographs. “After preservation, a picture won’t really do it justice,” he says.

Then Maclaine will send his drawings to the world’s leading anglerfish expert, Ted Pietsch at the University of Washington, to see if he has, indeed, found a new species.