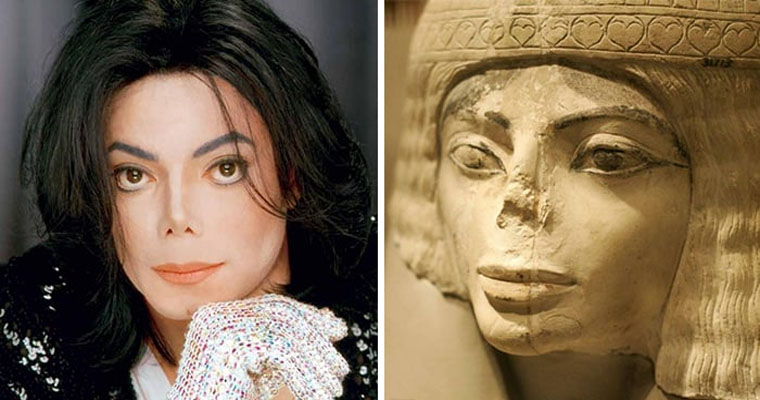

A juvenile Maya maize god is portrayed, which is consistent with earlier representations of headless Maya deities.

Last summer, researchers in Mexico were startled to discover the tip of a gigantic nose protruding from the ground while excavating a part of the ancient Maya metropolis of Palenque.

At El Palacio, nostrils, a chin, and the parted lips of a mouth appeared as they carefully cleared away additional debris.

The 1,300-year-old stucco head representing a child Hun Hunahpu, the Maya maize god, was made up of the ancient visage, according to Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

The discovery at the Palenque archaeological site, which is situated in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, is the first of its sort.

Arnoldo González Cruz, an archaeologist who participated in the excavation, says in a statement that “the finding of the deposit allows us to comprehend how the ancient Maya of Palenque constantly resurrected the mythological passage on the birth, death, and resurrection of the maize deity.”

The face emerged from an archaeological dig in Mexico. National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)

The face emerged from an archaeological dig in Mexico. National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)

The nine-inch-tall head had an east-west orientation that archaeologists believe represents the emergence of the maize plant at dawn, per INAH. They say Palenque’s Maya residents likely placed the large stone sculpture over a pond to symbolize the entrance to the underworld.

The sculpture was intended to depict a beheaded figure, echoing other Maya art depicting various headless gods.

Maize, or corn, was not only an important source of food for the Maya—it also played a fundamental role in their beliefs. According to the Popol Vuh, the Maya’s K’iche’-language creation story, gods created humans out of yellow and white corn.

As such, the Maya worshipped Hun Hunahpu, whom they believed was decapitated every fall around harvest time, then reborn the following spring at the start of the new growing season, as Ariella Marsden reports for the Jerusalem Post. Because of this pattern, the Maya also associated Hun Hunahpu with the cycle of human life and the changing seasons.

First domesticated about 9,000 years ago in what is now Mexico, maize played an important role in both Mesoamerican culture and the history of archaeology. As author Charles C. Mann writes in Maize for the Gods: Unearthing the 9,000-Year History of Corn, cobs of ancient maize discovered in New Mexico “were among the first archaeological finds ever carbon-dated.”

The head of a young Maya maize god was made of stucco and buried in a pond archaeologists think was once used for stargazing.

The head of a young Maya maize god was made of stucco and buried in a pond archaeologists think was once used for stargazing.

Archaeologists dated the stucco statue to the Late Classic Period of roughly 700 to 850 B.C.E. They believe it represents a youthful maize god because of the figure’s “tonsured,” partially-shaven haircut, which looks like ripe maize. This depiction of the deity was common at the time, per the Dallas Museum of Art, and symbolized “mature and fertile” corn.

When they first built the maize god’s pond, the Maya likely peered into it to study the reflection of the night sky. Later, researchers say, they symbolically shuttered the pond by breaking down some of the stucco and filling it in with shells, carved bone fragments, pieces of ceramics, obsidian arrowheads, beads, vegetables and the remains of animals, including quail, river turtles, whitefish and dog.

They topped the pond with a limestone slab, then surrounded it with three short walls and filled everything in with loose stones and soil.

Because it was preserved in a humid environment for such a long time, the divine head must now undergo a drying process, undertaken by INAH’s National Coordination for the Cultural Heritage Conservation, to preserve it. After more than a thousand years underground, the stone sculpture is being reborn—just like the beloved deity it depicts.