The Earth is a big place, and it has taken us a long, long time to fully map it. Today, it is easy to feel like the last of the great adventures is over, and we’ve found all that there is to be found.

For a long time though, this wasn’t true. As sailors set out to sail the seas and explore new regions, they were constantly making discoveries. But sometimes they made mistakes. As a result of navigational errors, mistaken observations, disinformation, and good old-fashioned human duplicity, errors were made. This resulted in the phenomena known as phantom islands. These are islands that were recorded on maps and believed to be real, but were later proven not to exist. These phantom islands led to a lot of confusion and many myths and legends over the centuries.

1. Thule: A Land North of Britain

Thule was first “discovered” around 325 BC by the Greek navigator Pytheas. He had been sent to explore northern Europe to identify the origin of all its trade. Pytheas set sail from his home port of Passalia (present-day Marseilles), when he sailed into the Atlantic and went north

What he found was Britain, which he recorded as Brittania or Prittania. Just north of Brittania, he found an island that he dubbed Thule.

Pytheas’s original writings have been lost, so unfortunately all we have to go on are the commentaries of geographers like Strabo. Some geographers believed Pytheas, while others were doubtful. Strabo wrote off Thule as an invention after reading Pytheas’s description of how the northern seas were full of ice.

Ptolemy, on the other hand, believed Pytheas, and in his world atlas, the Geographia, published around 100 AD, he included Thule. This work was translated by Florentine scholars in the 1410s and as such Thule continued to appear as a large island north of Britain on maps from this period well into the 17th century.

Of course, it was eventually found there was no large island north of Britain. It is believed that Pytheas had most likely either made it up or ended up on one of the Shetlands Islands , the Faroes, or had even sailed as far as Iceland or Norway. Another theory is that the island could have been Ireland. Either way, there’s no such thing as Thule.

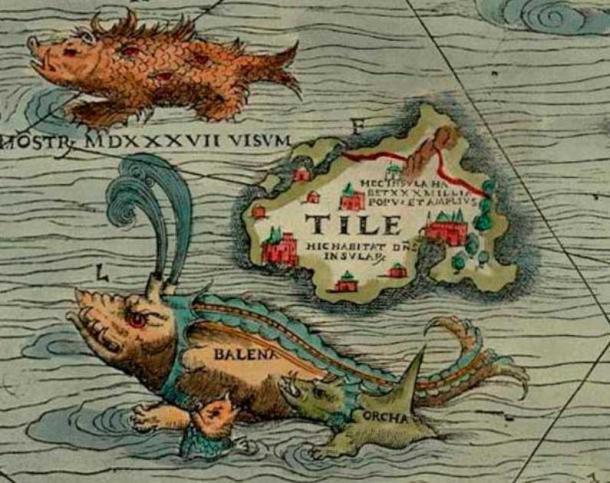

The phantom island Thule as Tile on the Carta marina of 1539 by Olaus Magnus, where it is shown located to the northwest of the Orkney islands, with a “monster, seen in 1537”, a whale (“balena”), and an orca nearby. ( Public Domain )

2. The Cassiterides: The Tin Islands

The first written mention of the Cassiterides (meaning Tin Islands) was made by the Greek writer Herodotus in around 430 BC. He had only heard rumors of the islands, but did not discount them as legends. He recorded them as where the ancient Greeks got their tin.

Later writers, like Posidinius and Strabo, attempted to locate the islands. They believed them to be small islands that were some way off the northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Posidinius and Strabo believed them to be the location of tin and lead mines, while Diodorus Siculus believed they merely received their name from their closeness to the tin districts of Northern Iberia. In short, no ancient writer was sure where they were.

How is it that the Greeks had no idea where their tin came from? Well, the tin trade was a closely guarded secret of the seamen of Gades (Cadiz in modern-day Spain) who controlled it. All the Greeks knew was that their tin came from the west, so therefore, there must be tin-rich islands somewhere to the west, which they hadn’t explored much yet.

Eventually, the Greeks discovered that most of their tin came from northwest Iberia and Britain. Neither of which matched earlier descriptions of the Cassiterides islands. The Greeks and Romans didn’t give up though. Rather than put down the existence of the Cassiterides as a misunderstanding, they chose to believe there were three sources of their tin. Iberia, Britain, and the still mysterious Cassiterides islands. They never found the latter.

Today, modern writers are just as stumped. Several small islands off of the British coast near Cornwall and the Iberian Peninsula have been suggested, but none fully match ancient descriptions.

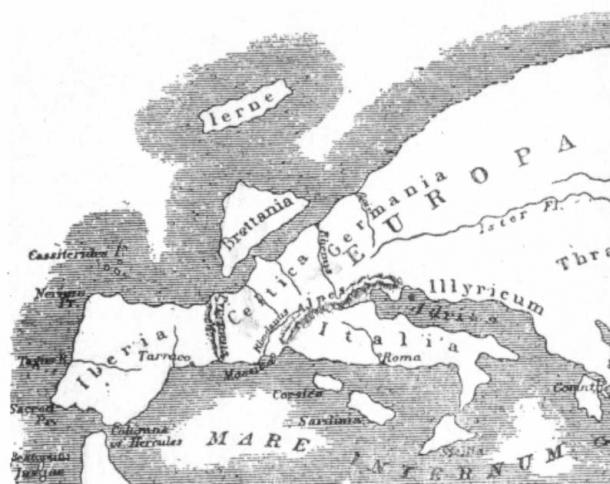

Map of Europe according to Strabo, with the phantom island of Thule shown to the north of Brittania. ( Public Domain )

3. Mount Penglai: Asia’s Mystical Mountains

It wasn’t just the ancient Europeans getting lost and making false discoveries. Their cousins over in Asia were doing the same. Mount Penglai is a legendary land that appeared in Chinese mythology as well as Japanese mythology (called Horai).

Mount Penglai was first recorded in the Classic of Mountains and Seas . The book is a Chinese classic text that covers geographical and cultural aspects of pre-Qin China and covers a whole host of Chinese mythology. It includes detailed descriptions of various mythological places, as well as descriptions of medicines, animals, and geological features.

Some of these descriptions are incredibly mundane, while others are fanciful and strange. As these myths are depicted as fact in the book, early Chinese scholars referred to it as a bestiary and believed it to be accurate. This led to Mount Penglai’s status as a phantom island.

The book describes Mount Penglai as being at the eastern end of the Bohai Sea on the east coast of China. According to ancient Chinese myths, this sea was home to three godly mountains. Penglai was one of them. These were said to be mountains where the gods lived.

Historically, efforts were made to find Mount Penglai. Qin Shi Huang, the founder of the Qin dynasty had his men search for the island during his quest for the elixir of life. Of course, he never found it. It is believed Chinese scholars may have gotten Mount Penglai confused with various mountains across Asia, such as those in Japan and the South Korean Peninsula.

“The Immortal Island of Penglai”, by Chinese artist Yuan Jiang, 1708 ( Public Domain )

4. Saint Brendan’s Island: A Holy Discovery?

Confusion over phantom islands continued long after the ancient period. As technology advanced and people became more adventurous and able to make long voyages, more and more phantom islands were discovered.

The story of Saint Brendan’s Island dates back to the early Middle Ages. It is named after Saint Brendan, an early Irish monastic saint, who claimed to have landed upon it in 512 AD, along with 14 of his monks.

Brendan and his monks reported that they celebrated mass there, staying for only 15 days. The ships that were awaiting their return, on the other hand, complained of waiting for a year for the saint and his men. They complained that while they waited, the island was concealed by thick fog the entire year.

The island was said to be in the north Atlantic to the west of northern Africa. Other monks attempted to find the island but were unsuccessful. This mystical island that was supposedly shrouded in fog and impossible to reach soon became the stuff of legend.

Much later, the Portuguese became interested in the island. During the 15th century, a famous Portuguese explorer called Henry the Navigator became convinced the island existed. He ordered a sea captain to visit the island but the man never returned. Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, repeated attempts were made to discover the island. Various sailors claimed to have come close to the island but were never able to land.

Up until the 19th century, sightings of this mysterious land were still being made, mostly by religious explorers such as the Scottish monk Sigbert de Gembloux in 1719 and a Franciscan friar in 1759. These sightings led to even more expeditions in the area.

Eventually, sightings of the island became less and less frequent until they stopped altogether. It no longer appears on any maps and has been classed as a phantom island.

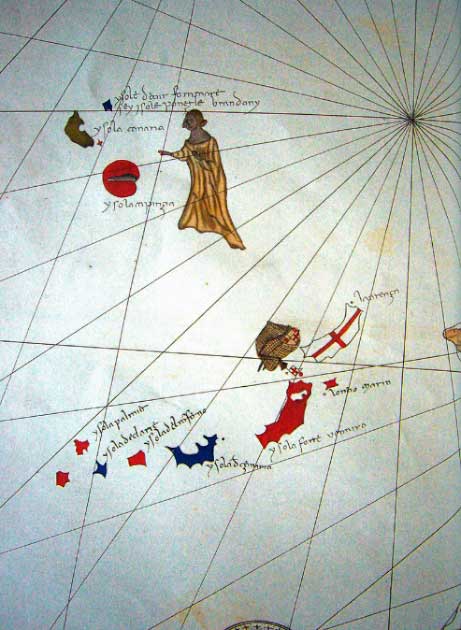

St. Brendan close to the island which bore his name depicted on a medieval map. On modern maps, there is no such island. It was supposed to have been located close to the Canary Islands. ( Public Domain )

5. Frisland: Proof You Can’t Always Trust a Cartographer

Some phantom islands are due to innocent misunderstandings and confusion between myth and fact. Other times, they’re down to simple human dishonesty. “Discovering” an island is a great way to make a name for oneself.

In 1558, a map and letter were released by the Venetian Nicolo Zeno. The letters were said to have come from two of his ancestors, Antonio and another Nicolo, who had reportedly sailed the North Atlantic at some point around 1400.

These letters were supposedly written by the first Nicolo to Antonio from Frisland. On the accompanying map, Frisland was shown to be around halfway between Norway and Scotland’s most northeastern point. In the letters, Nicolo claimed to be doing well and encouraged his relative, Antonio, to come and join him.

The legitimacy of these letters was called into question when they were first published, but this didn’t stop many cartographers from adding Frisland to their maps. Some cartographers went a step further and added bays, mountain ranges, and even towns to their maps of Frisland. The level of detail they managed was impressive, since Frisland never existed.

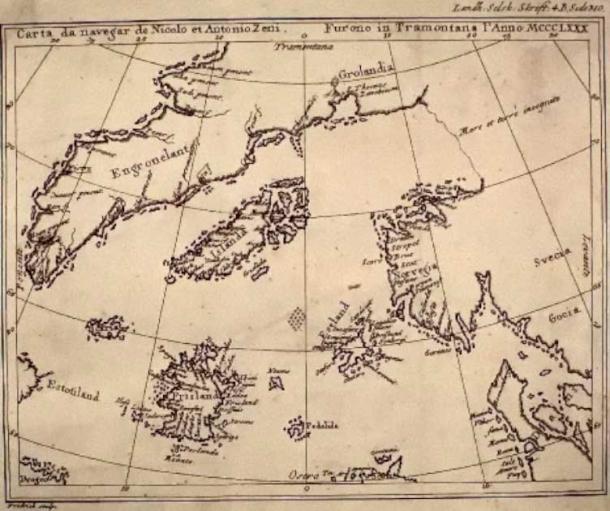

A reproduction of the Zeno map (original by Nicolo Zeno 1558), showing the phantom island of Frisland ( Public Domain )

6. The Island of California: Proof Cartographers Can Be Stubborn

Sometimes phantom islands stick around for a while, even after the evidence that they never actually existed has started to mount up. This is what happened with the Island of California.

The Island of California was first mentioned in the 1510 romance novel, Las Sergas de Esplandián, by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. The writer refers to the island as, “Know, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons”.

It is believed Rodriguez’s description of a place he had invented confused explorers when, in 1533, an expedition first discovered the southern portion of the Baja California Peninsula. The explorers were attacked by the natives and fled. They returned in 1535 and tried to start a colony, but it was short-lived. The limited information on the area they had discovered led to it being dubbed the Island of California.

Of course, in reality, the Baja California Peninsula is part of mainland North America, separated from the continent by the Gulf of California. It didn’t take other explorers very long to work this out. Over the following years, other explorers landed in the area and realized the ‘Island of California’ was probably a phantom island.

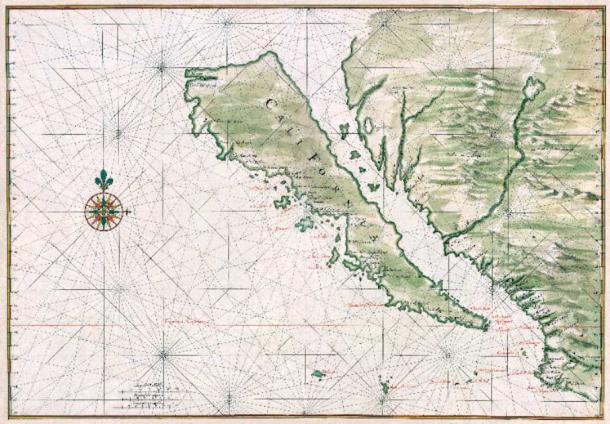

Despite mounting evidence that the Island of California didn’t exist, it took a long time for the fact to filter down to cartographers. The island first appeared on maps in 1622, by which point evidence against it was already mounting, and stayed on maps well into the 18th century.

Map of the phantom ‘Island of California’, circa 1650 ( Public Domain )

7. Hy-Brasil: Another European Phantom Island

Brasil, or Hy-brasil as it was known, was a phantom island that people believed was located in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. Much like Saint Brendan’s Island, it was said to be shrouded in mist most of the time, making it impossible to reach.

Hy-Brasil first started appearing on nautical charts way back in 1325. Over the next few hundred years, various attempts were made to visit this mysterious phantom island. It was widely spread that the island was only visible one day every seven years. Expeditions left Bristol in 1480 and 1481. A few years later, John Cabot , a well-known Italian navigator, and explorer claimed to have visited the island.

In 1674, another navigator, Captain John Nisbet, said he had seen the island while journeying to Ireland from France. He claimed to have seen large black rabbits on the island, ruled over by a magician who lived in a stone castle. The only problem was it was a literary invention by an Irish author, Richard Head.

The hunt for Hy-Brasil was largely abandoned during the 19th century. In 1862, a shoal in the Atlantic Ocean known as Porcupine Bank was found 120 miles west of Ireland. Ever since it has been suggested that this may be Hy-Brasil.

Brasil (far left) as shown in relation to Ireland on a map by Abraham Ortelius, 1572 ( Public Domain )

Conclusion

Many of the phantom islands come from an exciting period of history when countries were frantically exploring our planet’s oceans and adventuring in previously unknown lands. Today that spirit of adventure is sadly becoming increasingly rare as we have mapped much of our planet. Satellites have ruined the fun.

But there are still pockets of lands in the most remote parts of the world where modern humans still hasn’t set foot. Humanity has always had a sense of adventure. There is no reason to believe that will change.

To feed this hunger, today we plunge into the deepest depths of the oceans and look skyward toward space. It is exciting to think about what discoveries lay ahead of us, even if some of them may ultimately turn out to be phantoms.